Part III: Stalin & Beyond

Legitimacy through Association

With the death of Lenin in 1924, debate among the political elite arose as to who would be his successor. Although Lenin’s testament declared Stalin as an unsuitable political heir, Stalin’s control over the bureaucracy allowed him to succeed as the new leader.[1] In order to ease the public’s transition to the new dictator, visual propaganda promoted Stalin’s legitimacy as rightful ruler. A cult of hero-worship was developed surrounding Stalin which was appropriated from the previous Leninism. While poster artists such as Klutsis employed iconic socialist figures as a means to legitimize Stalin’s rule, the emerging official style of socialist realism gradually dismantled the symbolic power of Lenin as the premiere Soviet leader. Through Stalinism, the iconography of Lenin in the Soviet poster came to represent the socialist past rather than its future.

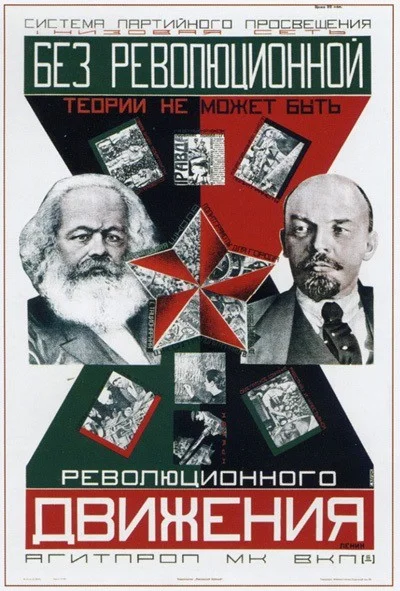

During the Post-Lenin epoch, poster art equated Marx with the intellectual sphere of socialism while Lenin represented political precedence. In Klutsis’s poster There can be no revolutionary movement without a revolutionary theory, the official cliché [2] of Marx and Lenin are depicted side by side. The historical figures are made more tangible by the graphic clarity of photomontage that suggests a ‘mortal body’ with a divine presence.[3] The subtle radial design created by the blocks of color and the central Soviet star visually reminds the viewer of the centrality of the socialist figures to communist belief. Through the transformation of the ‘reality’ of photography[4] into visual fiction, the iconic images of Marx and Lenin are combined to create continuity between socialist theory and communist practice.

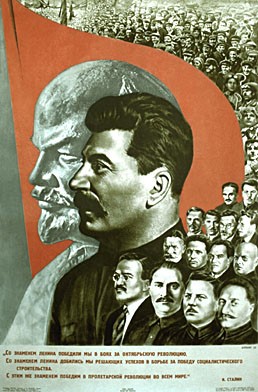

This image of Soviet dogma is reused by Klutsis to include Stalin in Raise the banner high of Marx, Engels, Lenin, and Stalin!. Klutsis’s constructivist poster validates Stalin’s new authority as the Soviet leader by situating him within a pantheon of communist heroes.[5] By juxtaposing Stalin next to a chronology of great socialist thinkers, Stalin is presented as the next successor in the legacy. Although each figure appears separately on a communist red banner, they are unified by the support of the collective which appears below the flag in various perspectives. This claim to legendary status is further accentuated by the monumental size of the banners in relation to the small scale of the Soviet masses. Such a manipulation of artistic space and composition provides a surrealistic effect in which the temporal and ethereal are blurred.[6] Consequently, the cult worship of Stalin is given an appropriate propagandist context through a mythologizing of the historical past.

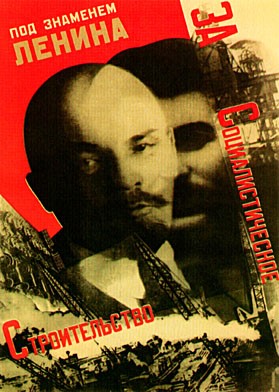

In order to propagate Stalin’s new authority with the masses, Klutsis continued to formally experiment with the visual link between Lenin and Stalin. The previous scene of Raise the banner high of Marx, Engels, Lenin and Stalin! in which the crowd supporting banners of the communist leaders has been rearranged into an angular construction in Under Lenin’s Banner for Socialist Construction. This abstraction of figurative representation provides Klutsis with the opportunity to visually merge the photographic images of Lenin and Stalin; such a metonymic device served to accentuate the idea of a ‘hyphenate cult of an infallible Lenin-Stalin.’[7] Although the layering of the two faces has a ghostly effect, Lenin’s face is more visible allowing him to be the central image yet not the focus. In 1931, Klutsis was censored by the Central Committee of the Communist Party for the technicality of his photomontages because they were viewed as ‘impersonal’ representations during a time when official art demanded a new humanist realism populated with heroic individuals.[8] Although restricted in artistic production, Klutsis remained committed to exploring the visual relationship between the two leaders as seen in his poster of 1933. Stalin’s plans to replace Lenin as the hero of communism became increasingly evident as illustrated by the superimposing of Stalin’s profile over Lenin’s. While Lenin continues to be a ghostly presence, Stalin has returned to a material (and heroic) existence as he heads the front of a more legible collective. The compulsory change in Klutsis’s style foreshadows not only the eradication of constructivist experimentation in Soviet posters, but also the visual purging of Lenin.

Gustav Klutsis, Under Lenin’s Banner for Socialist Construction, 1931 and "Under the Lenin's banner we fought. victoriously in the October revolution. Under the Lenin's banner, we obtained the decisive success in the fight for the of the socialistic construction. We become it even under this banner, 1933

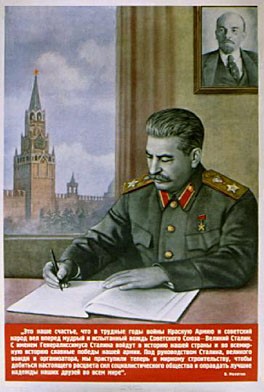

As the aesthetic principles of socialist realism developed, Lenin’s visual role as Soviet leader is subordinated to Stalin’s development of his own iconography. In contrast to the Klutsis’s constructivist posters in which Lenin has a significant role despite the leader’s death, the stylized realism of Grigor'evič portrays Lenin as a subsidiary to Stalin. The two men reside in separate illusionist spaces, one in which Stalin is depicted working within an interior setting while a portrait of Lenin hangs on the wall in the secondary space. The figurative arrangement signifies the phasing out of Leninism as a progression of Stalin’s own cult of personality in poster art.[9] With no verbal acknowledgement of his predecessor, Stalin’s primary importance as the true Soviet leader is emphasized. Instead, Lenin’s presence is evoked through a portrait in the background alluding to the way in which reverence was paid to previous Russian icons - Orthodox saints.[10] Similar to the manner in which the Orthodox religion provided devotional images of martyrs, Soviet propaganda posters employed posthumous images of Lenin as a means to encourage Soviet devotion and loyalty. In comparison to the rest of the composition, the diminutive size of the hanging portrait indicates that Lenin remained an object of veneration during the 1930’s to 1940’s. Although Lenin’s star was great, it was steadily smaller and dimmer next to Stalin’s.[11] While Klutsis depicted the immortal Lenin as if living within the pictorial space, Grigor'evič underlines Lenin’s physical absence by portraying him as a picture within a picture.

In contrast to the agitational context surrounding the imaging of Lenin’s leadership, Stalin’s regime is portrayed in a more passive style of socialist realism. From Klutsis’s dynamic photomontage to Grigor'evič’s static illustration, references to the exertion of mechanized labor through the proletariat are replaced with the visual calm of the relaxed body of Stalin.[12] As Stalin’s position as Russia's communist leader became more secure, his visual body is no longer fused into the setting[13] as exemplified by the wall which separates the leader from the public domain. Although situated in a domesticated context, the military status of Stalin is implied by his uniform while his bureaucratic duties are indicated by his concentration in writing. By evoking the coloring of legendary Lenin in the background, and through Stalin’s monochromatic pallor, superhuman qualities are visually bestowed on the living leader. While socialist realism depicts the resemblance of Stalin straightforwardly, his iconic meaning as the hero of the proletarian movement is indirect. As evidenced by Grigor'evič’s poster, the development of socialist realism marks a visual shift from the representation of leader as living myth (Lenin) to images of a leader who is constructing a myth (Stalin).[14]

With Stalin’s death in 1953, the visual presence of Stalinism rapidly disappeared while Lenin’s image continued to evoke legitimate rule. The sudden departure of Stalin from Soviet iconography can be explained by the comments made by the succeeding leader Nikita Khrushchev in his Secret Speech of 1956. In his speech, Khrushchev criticized Stalin’s autocratic regime while maintaining support for the original ideology of Lenin’s rule. Through the official denouncement of his predecessor, Khrushchev debunked Stalinism thus allowing the visualization of Lenin to be reinvigorated. As seen in the poster Our goals are determinedly clear, the tasks. Work, comrade!, Khrushchev continued the poster tradition of employing Lenin’s image as a signifier for political legitimacy. Unlike the socialist realism promoted under Stalin, Khrushchev did not attempt to replace the symbolic meaning of Lenin with his own image. Without developing a strong cult of personality, Khrushchev was easily replaced by Leonid Brezhnev in 1964 who was then succeeded by Mikhail Gorbachev in 1985. During this period of rotating Soviet leaders, Leninist imagery provided constancy and continuity within the visual realm of the poster. In contrast to the declining economic circumstances of the communist state during the 1980’s, propaganda maintained its message of social progress. In The Party we do follow, the success of Soviet solidarity is presided over by the face of Lenin as the idealized collective stride forward. The totality of modern achievement is embodied in the depiction of social stereotypes dressed in contemporary attire such as the doctor (technology), the worker (industry), the farmer (agriculture), and the soldier (military). Nikolaevich employed the direct gaze of both the leader and the citizenry as a means to include the viewer in the Soviet advancement. While the Soviet poster’s representation of current authority dissipated following the end of Stalinism, Lenin’s image as the founding-father became associated with the collective rather than that of a ruler. Although communist leadership changed repeatedly until the dissolution of the Soviet Union in 1991, Lenin’s visual legacy as an emblem of Soviet ideals continued.

As the artistic transition from the avant-garde to socialist realism occurred, the visual language of the Soviet poster radically altered in format. Rather than depict Lenin as an icon of utopic progress, Lenin is portrayed as a legendary figure of the past. Although Stalinist censorship narrowed formal experimentation as exemplified by Klustis, poster artists such as Grigor'evič were encouraged to extend communist history into a mythic narrative. Whether associated with by-gone socialists or represented as a devout portrait, the original iconic meaning of Lenin was re-contextualized to support Stalin’s dictatorship. This visual persuasion to replace one political hero with another during Stalinism is eradicated as a succession of leaders consistently employed the image of Lenin as a way to legitimize their rule. Through the viewer’s visual familiarity with Lenin, the Soviet poster was able to convey political stability despite changing leadership.

Enjoyed reading? Subscribe to our newsletter.

Ahlstrom Appraisals | Personal Property Appraisals and Art Consultations | Serving Atlanta & Southeast | Fine Art, Antiques & Vintage

WHOSE LENIN IS IT ANYWAY? WILL CONTINUE IN THE NEXT POST

“PART IV: post-socialism - Critique through lenin”

[1] John Thompson, Vision Unfulfilled: Russia and the Soviet Union in the Twentieth Century, (Independence, KY: Cengage Learning), 243.

[2] Margarita Tupitsyn, Gustav Klutsis And Valentina Kulagina: Photography And Montage After Constructivism, (New York: Steidl / International Center of Photography), 66.

[3] Rachel Rosenthal, “Visual Fiction: The Development of the Secular Icon in Stalinist Poster Art,” Stanford’s Student Journal of Russian, East European, and Eurasian Studies (vol. 1, 2005), 5.

[4] Ibid., 12.

[5] Ibid., 5.

[6] Ibid., 12.

[7] Victoria Bonnell, Iconography of Power: Soviet Political Posters under Lenin and Stalin (London: University of California Press, 1997), 157.

[8] Leah Dickerman ed., Building the Collective: Soviet Graphic Design 1917-1937 (New York: Princeton Architectural Press, 1996), 34.

[9] Rachel Rosenthal, “Visual Fiction: The Development of the Secular Icon in Stalinist Poster Art,” Stanford’s Student Journal of Russian, East European, and Eurasian Studies, 6.

[10] Ibid. 2.

[11] Victoria Bonnell, Iconography of Power: Soviet Political Posters under Lenin and Stalin, 161.

[12] Leah Dickerman ed., Building the Collective: Soviet Graphic Design 1917-1937, 36.

[13] Margarita Tupitsyn, Gustav Klutsis And Valentina Kulagina: Photography And Montage After Constructivism, 66.

[14] Ibid., 63.