Part II: Leninism

Stance towards the Future

Once the personage of Lenin and the theme of a global world order were established, Lenin evolved into the "hero" of Soviet poster art. This mythologizing of Lenin coincided with the increasing centralization of authority in the state. The Soviet Union’s desire to quickly transform backwards Russia into a modern nation resulted in posters which focused on urban development. In order to imply public support for industrialization policies, state propaganda portrayed Lenin as a heroic figure overseeing economic and military improvements. Amidst these new industrial settings in posters, Lenin are credited with the advancement of society through visual means such as gesture and pose, the motif of light, and the spatial relationship with respect to other figures. As the communist government transformed the city centers, the soviet poster metamorphosed Lenin’s image into an emblem of progress. By examining the use of light, pose, and placement, Lenin, emerges from the poster as a Soviet hero.

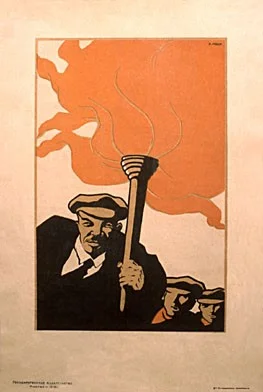

One of the simplest means to indicate Lenin’s role in society’s advancement was through the depiction of light in its various forms. The idea of enlightenment through revolution is illustrated in the early 1919 poster, Lenin with the torch by Stachievič. In this poster the leader, Lenin carries a torch to illuminate the way to a brighter future. The use of a classical light torch is paradoxical as this archaic symbol[1] signifies a radical future. The magnitude of the flame’s brightness is conveyed as an orange block of color occupies most of the pictorial space. Lenin is holding the torch as he directly gazes at the viewer with a tilted pose that implies forward movement. The position of the two workers behind the leader not only indicates an emerging political hierarchy, but the spatial distance also contributes to the sense of dynamism as a diagonal line is formed through the figurative arrangement.

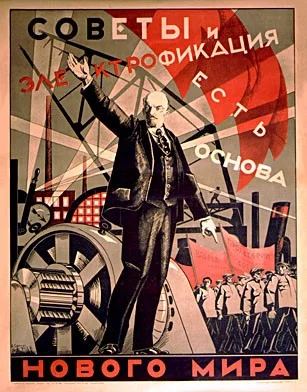

The concept of light as a symbol for social progress is modernized in Niolaevič’s poster in which fire is replaced with electricity. The source of light in Soviets and electrification are the basis for the new world originates from the industrial setting. As the title clearly indicates, technological advancement, beginning with Lenin’s Plan of Electrification in 1920, was seen as a crucial factor in creating the ideal Soviet society; Lenin had even described the proletarian state’s plans for electrification as “the final victory of the foundation of a civilized life without exploiters.” [2] The government’s plan for electrification is represented as an exciting change as evidenced by the optical effect of the diagonal bands of light; the proliferation of diagonals also serves to visually express industrial and economic dynamism.[3] In comparison to Stachievič’s pair of workers, the number of proletariat figures in Niolavis’s depiction has multiplied in order to create a stronger sense of mass movement and therefore mass public support for the rapid industrialization. The male crowd’s uniformity of dress and wide stance suggest a forward military march, yet a distance is maintained between Lenin and the collective as he appears separately in the central space of the foreground allowing the scale of the leader to seem monumental in comparison. Through Lenin’s hand gestures, the cause and effect of modernization is indicated. In order to convey the success of the Electrification Plan, the leader’s right hand points to Soviet solidarity while the left hand is raised upwards towards the collective outcome of electric illumination. As can be seen, the visual significance of light in association with Lenin is transformed from political enlightenment to technological advancement.

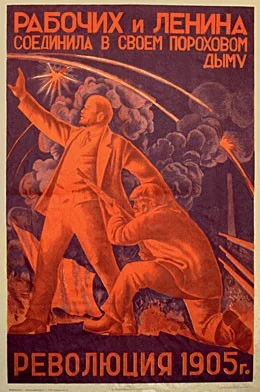

In the commemorative poster The workers and Lenin brought together in the revolution of the year 1905 in its powder and smoke, the more elemental form of light reappears as an explosion of revolutionary battle. The orange flares illuminate the purple darkness so that viewer can observe the interaction between Lenin and the socialist rebel. By positioning the revolutionary in the foreground, Niolaevič provides spatial unity between the two figures while maintaining political rank. Thus, Lenin’s previous pose in the electrification poster is given new patriarchal meaning as his right hand rests on the revolutionary’s shoulder in a fatherly manner. The representation of the proletarian collective as a militarized work force becomes increasingly developed in later posters in order to convey the hegemony of the working class.[4] Similar to the figurative arrangements mentioned previously, a diagonal is created in which ascendancy is accentuated by both the rebel’s rifle and Lenin’s raised palm. While the implementer of progress changes according to the level of militancy represented, Lenin is consistently portrayed looking toward the future with light illuminating his guidance.

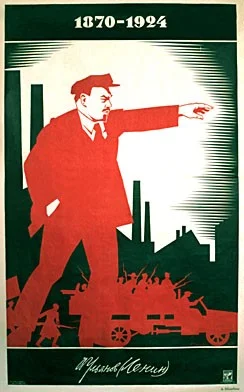

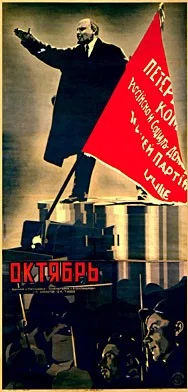

In order to persuade the public that progress was through communism, the image of Lenin looking towards the future became a standard means of projecting a better tomorrow. Despite the use of the same pose, political posters continued to stylistically differ in their representation of the growing veneration of Lenin as exemplified by Ulyanov’s Lenin and Klutsis October. Through schematic gesticulation, the leader appears at ease yet focused with his right hand casually placed in his pocket while his left arm directs the viewer to a space outside the visual domain which can only be reached through Lenin’s guidance. The popular color scheme of red, white, and black in Soviet posters not only allowed for cheaper production, but also emphasized the symbolism of ‘Red Russia’.[5] Both Ulyanov and Klutsis stress the Soviet Leader’s importance through a striking red contrast; Lenin and the collective, arrayed as army-like fronts,[6] are unified through color in Lenin while the abstracted red backdrop of October allows the glorified figure to boldly stand out. In Lenin, the common details of a cityscape and militia are reinterpreted into a series of outlines which highlight the distorted scale of the monumental Lenin in the foreground.

While Ulyanov enlivens the image by employing the flat language of lithography, Klutsis reinvigorates the depiction of the communist icon through photo montage. The realistic effect of the photographic representation of Lenin suggests an objectivity in which the propagandist function of the image is veiled. Klutsis’s innovative method of collage extended the representational terrain of the iconic Lenin[7] in which the embodiment of socialist utopia appears in a documentary format. Although Lenin and October stylistically contrast, both works utilize formal elements of the poster medium to revitalize Lenin’s stereotypical pose. Thus, the popular representation of Lenin in a forward stance reveals the increasing idol worship of his ‘political body.’

As Lenin became more myth than man, his elevated position grew more visually apparent. Lenin’s fame as an accomplished orator became an effective vehicle for poster artists to depict him as the political leader amidst the public. In A ghost wanders about Europe, a ghost of communism, the role of the speaker demonstrates Lenin’s conviction to the political ideology he leads. Lenin stands behind a parapet in which a podium is suggested through the grainy detail of the yellow material as well as the hand’s grasp of the ledge. Although the audience is unseen, the context of a workers’ rally is indicated by the red and white banners and the nearby factory building. Even though the poster was produced while Lenin was still alive, the text defines the leader as a spirit of communism; this mystic characterization is further emphasized by the ghostly effect of a monochrome figure surrounded by red and yellow. As this early representation of Lenin at the podium reveals, the context of public address becomes an effective method to portray the communist leader amidst the crowd.

Rather than portray Lenin as a statesman presiding over the proletariat, Timofeevič’ depicts the scene in October as a dictator above the crowd. Only after Lenin’s death did crowds begin to appear in the poster setting signalling the increasing public veneration of the leader which was taking place in Soviet iconography.[8] With Lenin situated on top of a military tank in October, the political hierarchy is clearly shown as spatial distance is created between Lenin and the crowd. The patriarchal nature of society is indicated by the inclusion of only male figures with Lenin as the father. Through the verticality of the poster, the regime’s social stratum is implied and Timofeevič’ creates a separation between the leader and the masses by a military platform. Thus, the hierarchical value of Lenin is translated into ‘perspective into a symbolic space.’[9] Timofeevič’s visual treatment of Lenin’s physical and social position evokes a heroic statue on a pedestal rather than a public orator at the podium. This sense of the statuesque is taken literally by Markianovič in his Social Realist poster. The presence of Lenin is conveyed by a statute of the former dictator in the background while a banner of the current ruler Stalin hovers above the idealized collective in the foreground. Markianovič employs the iconic Lenin to further legitimize Stalin’s rule. The change in political authority, however, is illustrated by the more prominent position of Stalin’s image as compared to the recessed positioning of Lenin’s image. Thus, the increasing distance between Lenin and the crowd in Soviet posters reveals his changing status in the totalitarian regime.

In examining Soviet propaganda, it is apparent that Lenin’s significance as a communist icon extends beyond political leadership. Through the use of light, pose, and placement, Lenin’s status as a heroic figure becomes increasingly monumental and symbolic in its changing perspective and spatial distancing. While the leader’s hand gestures direct the viewer to the government’s role as the instigator of technological advancement, the depiction of light in association with Lenin signifies the economic success of industrialization. Soviet consolidation of power is also expressed through Lenin’s elevated position above the military crowd. This visualization of political hierarchy continued to be employed as evidenced by Stalin’s emulation of Lenin’s superhuman image. Thus, the heroic portrayal of Lenin as a means to indicate societal progress subtly reveals the growing military-industrial complex of the Soviet Union.

Enjoyed reading? Subscribe to our newsletter.

Ahlstrom Appraisals | Personal Property Appraisals and Art Consultations | Serving Atlanta & Southeast | Fine Art, Antiques & Vintage

WHOSE LENIN IS IT ANYWAY? WILL CONTINUE IN THE NEXT POST

“PART III: Stalin & Beyond - Legitimacy through Association”

[1] Victoria Bonnell, “The Representation of Women in Early Soviet Art,” Russian Review, vol. 50, 1991, 269.

[2] Leah Dickerman ed., Building the Collective: Soviet Graphic Design 1917-1937 (New York: Princeton Architectural Press, 1996), 13.

[3] Rachel Rosenthal, “Visual Fiction: The Development of the Secular Icon in Stalinist Poster Art,” Stanford’s Student Journal of Russian, East European, and Eurasian Studies (vol. 1, 2005), 6.

[4] Dickerman, Building the Collective: Soviet Graphic Design 1917-1937, 30.

[5] Rosenthal, “Visual Fiction: The Development of the Secular Icon in Stalinist Poster Art,” Standford’s Student Journal of Russian, East European, and Eurasian Studies, 2.

[6] Jeffery T. Schnapp, Revolutionary Tides: The Art of the Political Poster: 1914-1989 (New York: Skira, 2005), 13.

[7] Bonnell, Iconography of Power: Soviet Political Posters under Lenin and Stalin, 61

[8] Ibid., 147.

[9] Ibid., 143.