Part IV: Post-Socialism

Critique through Lenin

With the end of the Soviet Union in 1991, Russian society started to integrate itself into a global culture. Governmental policies, such as Perestroika and Glasnost, opened insular Russia to economic and cultural exchange at an international level. Meanwhile, the government’s support for official art was replaced by a growing post-communist movement in which the graphic language of propaganda posters was employed to visually critique the Soviet legacy. From the critical posters of Vasil'evič to the journalistic photographs of Filonov, the standard language of public Soviet art was transformed into thematic codes whose meaning had greater variation according to context. As exemplified by the works of Kosolapov, the icon of Lenin became a popular motif that was combined with consumerist imagery in order to satirically describe Russia’s transition into a different type of mass culture. As revealed by the critical artwork created during the post-communist era, dissident artists began to employ Lenin’s image to convey public disapproval rather than signifying collective support.

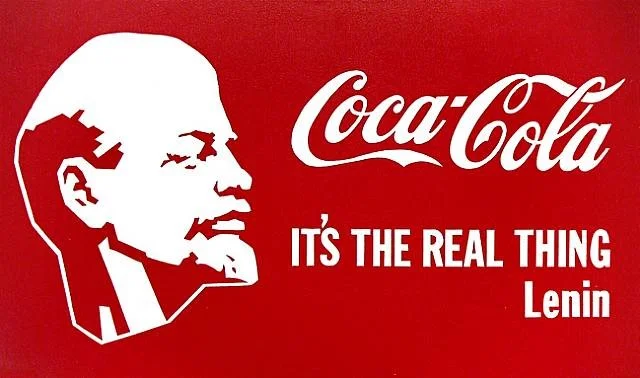

Rather than create a new visual lexicon, the Sots artist Kosolapov appropriated from existing Soviet signifiers.[1] For instance, the symbol of Lenin was employed to create an effective social critique in the works McLenin’s Next Block and Lenin Coca-Cola. With Lenin's recognizable profile combined with the commercial logos of McDonald’s and Coca-Cola, these emblems are transformed into cultural symbols of the East versus West didactic. With the end of the Cold War, Russian society was no longer insulated but instead apart of the globalization process. This dismantling of the Soviet society occurred with the implementation of the Perestroika policy which included the replacement of the collective economy with a market economy; as Kosolapov once commented in an interview, “My design of ‘Coca-Cola’ became a symbol for the Cold War. Another design ‘McLenin’ in some measure became a symbol of perestroika.”[2] This dramatic transition from nationalism to internationalism is conveyed through Kosolapov’s inversion of the Soviet global narrative geared towards a national audience into a local narrative with a worldwide audience. Unlike the totality of soviet art with ‘socialism in one country,’ the dissident art of Kosolapov employed symbols of the outside world as a means to de-mythologize Soviet reality.[3] The clash of economic ideology even manifested itself in the handling of the poster medium. Although painted, the works appear as if mass-produced through Kosolapov’s use of a graphic style. The formal elements of graphic art are evident in the flatness of Lenin’s profile and in the use of the standard typography of advertising. By employing the recognizable English text as a means to evoke American popular culture, words become real material objects, much the way Lenin’s resemblance was transformed into the object of a real superhuman.[4] Consequently, the contrasting ideological symbols of capitalism and socialism are effectively fused through the manipulation of the public language of advertising and propaganda.

By superimposing the commercial signs of American capitalism onto Soviet propaganda, Kosolapov satirizes socialism’s claim as a world movement. While communal ownership on a national scale ended in Russia, privatization thrived as exemplified by the pervasiveness of the American market through the trans-national companies of McDonald’s and Coca-Cola. Thus, the failed dream of Leninism is wittily placed side by side with its ideological enemy of capitalism. This irony is further revealed when Kosolapov’s works are compared with Nikolaevich’s Comrade Lenin cleans the land from garbage. While both artists use the image of Lenin to comment on international relations, late-socialism perverts the dictator’s previous influence as leader of world communism. In both McLenin’s Next Block and Lenin Coca-Cola, the figure of Lenin no longer revolutionizes world order by expelling its national enemies but rather is visually engulfed by the global influence of the consumerist market; such a post-modern representation of globalization is described by the artist as being, “about Russian culture in the context of internationality.”[5] By placing Lenin within a commercial context, Kosolapov visually comments on how the international movement of the proletariat has been subjugated by the very principles it was fighting. Thus with the end of communism in Russia, the revolutionary leader of socialism has become another cultural brand.

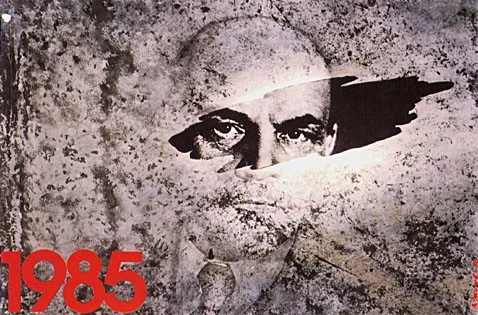

With the collapse of the Soviet Union, artists began to depict communism’s waning cultural influence through the fading face of Lenin. In Vasil'evič’s poster titled Lenin (the traditional direct representation of Lenin is subverted by placing the figure behind a layer of grime. The suggestion of a dusty surface, which separates the leader from the viewer, implies Lenin’s growing lack of political relevancy in the workings of society. Thus, the previous ‘fantastic’ power of Soviet symbolism had been negated with the dismantling of communism.[6] Lenin’s well-known gaze remains visible as if dirt has been swept away. Despite the overall ambivalence projected, Vasil'evič’s allowance for eye contact indicates the symbolic presence of Lenin nevertheless remains in Russian culture. The graphic image of Lenin also appears in Vladimir Filonov’s 1993 photograph in order to describe the diminishing influence of Soviet rule. In this photo, Lenin appears as a faded image on an old billboard titled with the slogan “We will attain victory of the communist labor.” Similar to the dilapidation of the poster, the political message has lost its potency as the communist slogan has been reduced into ironic meaning. In contrast to the portrayal of industrial dynamism and proletariat solidarity in the Leninist posters of the 1920’s and 1930’s, the photograph conveys stillness and isolation; such dormancy is suggested through the temporal mood of a winter snow scene while the deserted town in the background further indicates a lack of activity and interaction. Thus, both works have situated Lenin in the background as an isolated figure separated by the passing of time. Unlike Ulyanov’s Lenin, the leader is no longer depicted by Vasil'evič’ and Filonov as the instigator of progress but rather a part of social decay; the crowd surrounding the communist hero has been replaced with the whiteness of snow and grime. Thus, the official image of a progressive Lenin has evolved into an archaic icon.

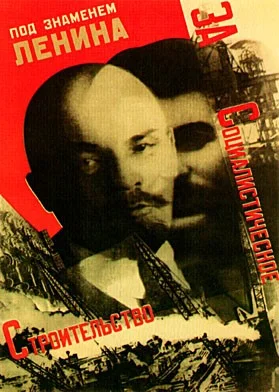

In Lenin-Stalin Marlboro, another ironic fusion of commercial and communist imagery can be seen. Kosoplavo de-mythologizes the traditional narrative of socialist realism by conveying the alliance between Lenin and Stalin through humorous means. Lenin and Stalin are shown as equals occupying similar roles in the composition while the conventional political slogan is replaced with the cigarette logo of Marlboro. Rather than appearing as god-like figures, the two men are depicted as comical characters through the incongruous setting of American advertising. The two dimensional quality of the Marlboro advert alludes to the flatness of the poster medium further underscoring the artificiality of the scene. Also, the communist color of red has been satirically reinterpreted into capitalist terms. Although situated as a backdrop, the Marlboro logo assumes a dominant role causing the interaction between the two dictators to be downplayed. In spite of the conflicting formal and political relations between the consumerist logo and the communist icon, the main aim of both symbols is to convince the population of their sincerity.[7] While Klutsis’s Under Lenin’s Banner for Socialist Construction of 1931 portrayed the relationship between Lenin and Stalin through avant-garde photomontage, Kosolapov did so through commercial illustration. Although both works have monochromatic figures, they appropriate different types of media (i.e. advertising versus photography) and their social commentary differs. The black and white pallor, which was popular in depicting the heroic leader in order to contrast him with the setting, is used by Kosolapov; however, the documentary feel of black and white in his parodist image is negated by the juxtaposition of color against the monochromatic figures. Thus, the pseudo-reality of the narrative is made evident to the viewer through Kosoplavo’s depletion of the symbols’ authenticity. By combining sources across temporal and geographical boundaries, the Stalinist historical narrative is deconstructed through the resulting pastiche of disparate cultural signifiers.[8] In the context of Sots parody, visual association with Lenin provides neither gravitas nor validity.

Although Lenin iconography no longer persuaded the Soviet citizen to participate in the proletarian movement by the end of the twentieth century, the leader’s image did continue to provoke the Russian viewer to actively consider the impact of the communist legacy. Depictions of a fading Lenin effectively visualized Russia’s transition away from communism into an era of social uncertainty. In contrast to the more ambiguous references concerning the Soviet past made by Vasil'evič and Filonov, Kosolapov blatantly parodies Leninist ideology.

Through combining the traditions of pop art and socialist realism, the nation’s entrance into global consumerism is satirically represented. By examining the methods of visual critique in early post-communism art, the image of Lenin is used not only to invalidate the idealism of Soviet propaganda, but also to dispel the icon’s own transcendental nature. Thus, the mythic Lenin is grounded through commoditization of art and society.

In Conclusion …

In twentieth century Soviet poster art, the image of Lenin portrayed not the man himself but rather an embodiment of communist leadership. Through the changing visualization of Lenin in the political posters of this era, the state’s influence on the social formation of Russia is revealed. This interplay between aesthetics and modern politics during the twentieth century allowed the graphic arts to aid in the cultivation (and later the dismantling) of a political idol. The initial Bolshevik iconography of the dictator reflected the government’s attempt to instill radical thought into the social structure both domestically and globally. As political ideology shifted, so did the depiction of Lenin. The Bolshevik leader gradually assumed a secondary role in response to Stalin’s political ascendancy. Through the stylistic replacement of the avant-garde with socialist realism in the portrayal of Stalin’s association with Lenin, the assertion of Stalin’s authority is revealed. While the depiction of the heroic Stalin ended with his death, Lenin continued to be employed by Soviet leaders as a symbol of political stability. With the dissolution of the Soviet Union, post-communist artists expressed their political dissent by undermining Lenin’s iconic presence in their subversion of the language of propaganda. Although Russian graphic artists throughout the twentieth century used various artistic styles, from avant-garde to socialist realism to pop art conceptualism, all employed symbols which were legible to their mass audience. Whether Lenin appears as a satirical character, a monumental hero, or a communist icon, his visual body continues to evoke significant cultural meaning in Russia. Indeed Soviet propagandists were quite accurate in their proclamation - “Lenin Lives!”

Enjoyed reading? Subscribe to our newsletter.

Ahlstrom Appraisals | Personal Property Appraisals and Art Consultations | Serving Atlanta & Southeast | Fine Art, Antiques & Vintage

[1] Sots art is a conceptual pop art movement that reacted against the Soviet aesthetic of socialist realism from the 1970s to the early 1990s.

[2] Maya Pritsker, M. “Any artist lives where he is popular,” Sotsart by Alexander Kosolapov, http://www.sotsart.com/2005/08/10/hudozhnik-zhivet-tam-gde-vostrebovan (2005).

[3] Ales Erjavec ed., Postmodernism and the Postsocialist Condition: Politicized Art Under Late Socialism (London: University of California Press, 2003), 60.

[4] Ibid., 34.

[5] Maya Pritsker, M. “Any artist lives where he is popular,” Sotsart by Alexander Kosolapov.

[6] Kate Kellogg, “Russian artists suggest alternative uses for political monuments,” The University Record, http://www.ur.urnich.edu/html (1992).

[7] Ales Erjavec ed., Postmodernism and the Postsocialist Condition: Politicized Art Under Late Socialism, 60.

[8] Valerie Hillings, V. “The Post-Utopian Art of Vitaly Komar and Aleksandr Melamid,” http://russian.psydeshow.org/images/komar-melamid.htm (2008).