Part III: Visual Access to the Harem Space

Similar to Orientalist writings, the limited access to the harem space caused its represented version in painting to be equally dissimilar to its real existence. Whether as an artist who resided in the Orient or the more common “armchair” Orientalist who remained in Europe, both painters often created their images of the harem in a studio space as was the common practice of all types of artists during the period. Despite the physical and culture distancing from the real setting, Orientalist artists attempted to incorporate accurate details in their artwork in order to suggest an authentic representation. Further, the way in which painters portrayed this secluded space was to idealise the harem into a place of privilege resembling more of a palace than a home. By elevating the domestic harem into a luxurious space, Orientalists provided an appealing setting for visual fantasy and were also able to gloss over the European disapproval of polygamy and Islam that was associated with the harem. Due to Western painters’ limited access to the harem for Western painters, its Orientalist depiction was increasingly idealised becoming less of a represented place and more of represented state of mind.

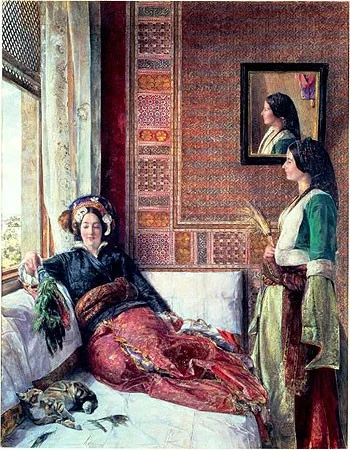

Even though John Frederick Lewis spent ten years in Cairo, almost all of his paintings, including The Reception, were created back in his English studio. Accordingly, Lewis relied heavily on his memories of Egypt for the setting, used his wife as a model, and utilised souvenirs brought back from the Near East to add veracity to the Orientalist scene. Lewis’s great grandnephew and biographer Michael Lewis describes the large collection of costumes his great-uncle had in his studio as painting aids..[1] These costumes are minutely portrayed in The Reception along with the microscopic stippling of pattern on pattern in the distinctly Oriental carpets and lattice window treatments; such attention to detail in the depiction of the accoutrements seemed in Lewis’s mind to compensate for the lack of study of the actual harem. In fact, his scrupulously detailed rendition of the room in The Reception is not even a depiction of the women’s quarters in a Muslim house, a mandarah, but it is actually a depiction of a men’s reception room.[2] By freely combining elements of architecture and costume, Lewis invented his own version of the represented harem. Like Lane’s translation of Arabian Nights and like many other Orientalists who had actually visited the Near East, Lewis created an authentic feel to his work despite it being based on educated conjecture.

Although Lewis left little in writing about the time he spent in Egypt, one of his guests, William Thackeray, wrote an amusing account (1884) of his experience of seeing a female servant in Lewis’s Cairo home in which“two of the most beautiful, enormous ogling eyes in the world” peered down at him through the lattices.[3] Such a verbal account reveals the more common Westerner’s experience of the Oriental home in which one can only observe the Oriental Other from the outside while being watched himself. Thus, it is interesting to see the contrast between Thackeray’s outsider description and Lewis’s depiction of the interior. Lewis provides the opportunity to see the lattice windows from inside the home both in Hhareem Life, Constantinople (1857) and Life in the Harem-Cairo (1858). Using the latticed woodwork screens (mashrabiyya) for the windows of the harem, which allowed its occupants to look out but prevent anyone from looking in; this is an accurate feature of the harem included by Lewis in his paintings, and it later became a favourite motif among British Orientalist painters.[4] Also, Lewis’s spelling of the harem as ‘hhareem’ in his titles such as Hhareem Life, Constantinople and his use of an Arabic inscription over the doorway was another way he added authenticity to his portrayal of the harem.

Similar to the interior images by Vermeer such as in The Love Letter (1670), the separation between the public and private sphere is subtly conveyed by Lewis through underlining the boundaries between outside and inside of the home. In Hhareem Life, Constantinople, the world outside the home can be partially seen through the latticed windows as the view of the outline of Ottoman buildings. Like the Oriental women’s limited ability to see beyond the harem’s interior, the viewer is limited to a partial view of the interior space as conveyed by the mirror in both of Lewis’s works. The mirror’s reflection in Inside the Harem-Cairo reveals an area of the harem room that is beyond the borders of the canvas, suggesting perhaps unseen inhabitants. The mirror in Hhareem Life, Constantinople is placed so that its reflection provides a partial view of the end of the seat with an ambiguous object placed there; also in Hhareem Life, Constantinople, the inclusion of the doorway with servants waiting to enter indicates the pampered lifestyle of the seated women and again suggests another room beyond the scope of the painting. Like Vermeer’s domestic scenes, Lewis provides a tinge of mystery to the narrative by including glimpses to spaces beyond the one that is centrally depicted. While the Oriental woman described by Thackery peers through the window to see the outside world, Lewis’s viewer peers through a visual ‘window’ to imagine Oriental domestic life. Nevertheless, the subject and viewer are both limited in the scope of their gaze a result of the gender boundaries of the harem.

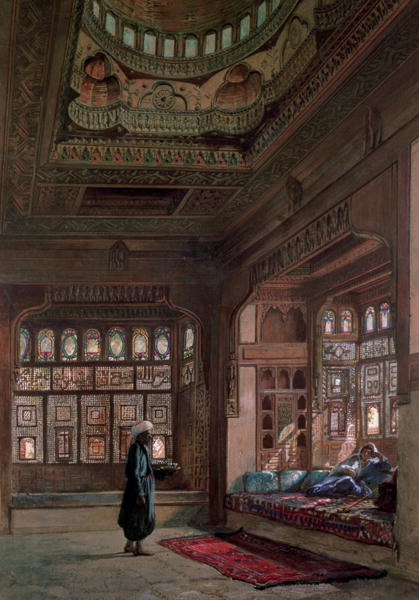

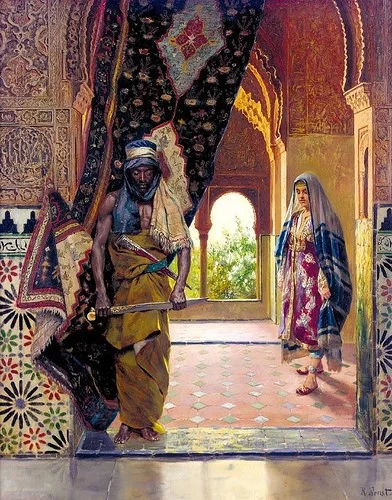

As mentioned previously, the domestic space of the harem was often transformed by Orientalist imagination into a palatial setting. In armchair Orientalist paintings such as Frank Dillon’s Apartment in the Harem of Sheikh Sadat (1870), the space of the harem is shown to be vast as the viewer’s position to the scene is from a great distance allowing the high ceiling of the room, which summits into a dome, to be viewed including the great distance between the eunuch and the lounging woman. Unlike Lewis, who portrays the harem as an intimate space with a subtle emphasis on its limits, Dillon creates a harem filled with an open and airy atmosphere that can be easily surveyed. Due to the emptiness of such spatial expanse, with the solitary female figure amongst a vast void of Oriental architecture, Dillon’s harem is more closely aligned with a palatial wing of the Seraglio than the women’s quarters of a typical Muslim home. In fact, Dillon’s portrayal of the harem is reminiscent of Beckford’s description of the wing of the caliph’s palace known as “The Retreat of Mirth” in Vathek. Another Orientalist painting which suggests a harem of palatial grandeur is Rudolph’s Ernst Guard of the Harem (1888), yet Ernst simultaneously underlines its forbiddeness. Through the figure of the foreboding eunuch who guards the entrance to the harem, restriction is underlined and is also reinforced by the curtain (a studio prop used by Ernst that was more likely a carpet judging by its pattern and texture) which is situated behind the eunuch. In addition, the inclusion of the floor outside the harem room is a restricting feature of the painting as the thick line of silver at the bottom of the composition further adds to the sense of spatial distancing the male viewer from the highly desired female subject. While the figure of the eunuch conveys separation in terms of gender and space, the Orientalist painting itself is another form of separation since it is an imagined representation and not a socially aware depiction of the actual harem. Similar to Lewis’s and Dillon’s portrayal of the eunuch as an obedient servant, Ernst portrays the eunuch as being demure in which he casts his eyes down in the presence of the Muslim woman, yet he is also ready to attack intruders with his weapons at hand; thus, the eunuch was used by artists to either embody the passivity of the Orient or its menacing violence. Although signs of forbbideness are incorporated in Guard of the Harem by Ernst, the viewer is nonetheless privileged to catch a glimpse of one of the Harem women as she appears on the other side of the entrance. Thus, Ernst provides a ‘so close and yet so far’ affect to his idealised harem image.

An interesting comparison to the male artists’ depictions of the harem space is Henriette Browne’s portrayal of the gendered sphere in The Arrival in the Harem at Constantinople (1861). Although respectable Muslim women were forbidden to pose for Western male painters, European women were occasionally invited to paint women’s portraits in the harems. [5] These images were never intended to be seen by men and were constructed entirely inside the harem. [6] In the case of The Arrival in the Harem at Constantinople, Browne was invited into the harem to create paintings of the women. In such a situation, the Muslim women were in control of their depiction of the harem environment. With fully clothed figures, polite gestures, and austerely undecorated spaces, Browne’s The Arrival in the Harem at Constantinople is closer in spirit to the images she also made of French nunneries.[7] In contrast to the highly decorated settings seen in male Orientalist works, Browne provides a space of austerity and emptiness with no allusions to a Sultan’s palace. While the spatial vastness in Dillon’s Apartment in the Harem of Sheikh Sadat conveyed luxury, Browne’s use of empty space denotes humble simplicity. In fact, the exotic setting is suggested by Browne only through the Oriental arches within the room and the simple dress of the women in which some remain veiled despite being indoors. Thus, Browne who focuses on the social interactions the female community, largely omits the visual dynamics of gender and spatial separation.

Even within an Orientalist painting, the harem remained allusive to the viewer. Issues of visual access to the Muslim female space were an integral part to Orientalist images in order to create further enigma surrounding the unknown life behind the harem walls. The intriguing lifestyle that was suggested, however, often idealised that harem space as a palatial setting as indicated by architectural details, the inclusion of servants, and the scale of the room. With the rare exception of a female Orientalist’s depiction of the harem, the seemingly authentic portrayal of the harem was in actuality a composite of the Western imagination and a study of various Oriental objects brought back to the studio. Thus, the gap between the real harem and the represented one grew ever more distant in Orientalist paintings, and the cultural insight reflected in these images was often a product of the Western mind in the guise of an Oriental study.

DISORIENTED IN THE HAREM WILL CONTINUE IN THE NEXT POST

"PART IV: The Male Voyeur in the imagined harem"

Enjoyed reading? Subscribe to our newsletter.

Ahlstrom Appraisals | Personal Property Appraisals and Art Consultations | Serving Atlanta & Southeast | Fine Art, Antiques & Vintage

[1] Caroline Williams, “John Frederick Lewis: Reflections of Reality,” Mugernas 18 (2001): 229.

[2] Ruth Yeazell, Harems of the Mind: Passage of Western Art and Literature (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2000), 225.

[3] Ibid., 225.

[4] Nicholas Tromans ed., The Lure of the East: British Orientalist Painting (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2008), 129.

[5] Mary Roberts, Orientalism’s Interlocutors (Durham: Duke University Press, 2002), 191.

[6] Ibid.,193.

[7] Ruth Yeazell, Harems of the Mind: Passage of Western Art and Literature (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2000), 222.