Part II: Locating the Real Harem, the Literary Seraglio

While examining the visual evidence, it is necessary to consider the social and literary background for the Western evocation of the harem as an eroticized space. Firstly, it is important to distinguish the actual reality of the harem in Arab society from the imagined reality of the harem in the Western mind. The harem, without its Orientalist context, is defined as the space of the Muslim household which was devoted to the female members of the family; these women included wives, daughters, servants, etc. Unlike the Western generalisation of the harem as a luxurious place inhabited solely by concubines with the occasional slave in attendance, a typical harem included all female members of different social status.[1] The implied eroticism that the notion of the harem acquired in the Western language is not seen in its original Arabic version; in fact, the derivative of the word harem means ‘forbidden’ or ‘sacred.’[2] It is this “forbiddeness” that was so appealing to the Orientalist. The bourgeois male was rarely permitted to catch a glimpse of the harem surroundings in reality and could only imagine this forbidden place.

Strictly speaking, in fact, there is no such place as ‘the’ harem, though the collective fantasizing often proceeds as if there were.[3] The specific form of the harem which was commonly evoked in 18th and 19th century literature could be described as an artistic interpretation of the Seraglio. The Seraglio was the imperial Turkish harem and a perfect setting[4] for the moral and material decadence that the Orientalists so desired in his image of the harem. Although a wealthy harem filled with hundreds of women did exist in the Seraglio, it was unique and, it too, was certainly forbidden to the Western gaze. Thus, even the travelling gentlemen aware of the Seraglio would have been prohibited to view or gaze upon it and accordingly, spurred on by privacy of the space, the disjunction between reality and fantasy continued in the evoked harem/Seraglio.

Most representations of the harem/Seraglio necessarily began not with direct experience but with prior representations, both visual and verbal.[5] In contrast with the actual gendered space of the harem in its Muslim context, the Orientalist Seraglio was represented as hyper-sexualized. When translated onto the page for a Western reader, the harem became the Seraglio, a site charged with erotic significance,[6] and consequently it was appropriated by authors as a means to discuss the morally taboo within their own society. This written formation of the imagined Seraglio was constructed in various literary forms including ‘translations’ of Arabic text, travel writing, and romantic novels. Through literature, the Orientalist made up for the lack of access to any type of harem through his imaginary written depiction of the space in which the western gaze could contemplate an intimate version of the harem/Seraglio at his reading leisure.

One of the most significant literary works to influence the Orientalists was Antione Galland’s 1712 French translation of Arabian Nights Entertainment or Arabian Nights. Galland was no mere translator; [7] he encouraged the Western phenomenon of Orientalism into a new spurt of creativity. The perceived decadence of the Near East was truly embodied in Galland’s “translation” of the harem scenes as seen in the tale of “Sweet Friend and Ali-Nur,” in which a woman bathes while assisted by numerous servants:

“After washing her hair and all her limbs, they rubbed and kneaded her, depilated her

carefully with paste of caramel, sprinkled her hair with a sweet wash prepared from

musk, tinted her finger-nails and her toe-nails with henna, burnt male incenses and

ambergris at her feet and rubbed light perfumes into all her skin. Then they threw a

large towel, scented with orange-flower and roses, over her body and, wrapping all

her hair in a warm cloth, led her to her own apartment…”[8]

This detailed account of a washing ritual filled with exotic scents, such as musk, indicates the sensuality that was associated with the harem. This collection of tales was originally part of an oral folkloric tradition whose audience sought bawdy entertainment. The fact that the Arabian Nights, with its fantastical description of the harem, originated from the actual culture of the Near East provides evidence as to why the erotic harem was not simply a Western invention. Although the recording of these tales was not considered to be a high form of literature in its original language, the translation of Arabian Nights was nonetheless seen by its Western audience as the epitome of the Oriental narrative, in which Orientalist writers incorporated a sense of exoticism to its already lascivious content.

In the 19th century, Arabian Nights had a revival in popularity with its English translations by W.E. Lane and Richard Burton. While Lane assumed the position of a scholar in his additional commentaries, Burton adopted the narrative voice of a well-traveled gentleman. In examining, Lane and Burton’s contrasting translations and additional commentaries, attention is directed to the complex influence of these fantastical tales on the Orientalist image in terms of the domestic and the erotic. Before Lane’s translation of Arabian Nights was published in 1841, he was already established as a reputable scholar of the Orient. In 1836, Lane had written about Egyptian culture based on his experiences in Cairo in An Account of Manner and Customs of the Modern Egyptians, and this work was regularly used by British painters as a reference in exhibition catalogues to lend authority to their images of Egyptian life.[9] With the success of his non-fiction writing, Lane translated Arabian Nights with the intention of making it into a family book. Lane’s dry tone in his relating of the tales conveyed an academic understanding while the soberness of his description allowed for the book to be well-censored and appropriate for a bourgeois family of listeners. Despite the sobriety of Lane’s version and commentary on the Oriental tales, he maintained a negative stereotyping of the Eastern women focusing more on their deceitfulness than their sexuality.[10]

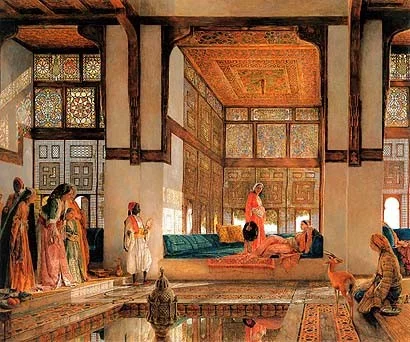

Like Lane, English painter John Frederick Lewis had also traveled to the East and used his experience to validate his portrayal of the harem in The Reception (1873). Lewis created the sense of the Orient in the The Reception scene through his use of ornamental details in the interior setting and in the women’s style of dress. The latticed work on the windows, the Persian rug on the floor the pool in the center of the room, and the geometric painted patterns on the walls were all unique to the Orient while the colorful robes and turbans worn by the women designate them as Orientals. However, because the women are clothed, albeit in Oriental garb, the traditional eroticism of the represented Muslim women goes unnoticed. Further, the overall scene conveyed in The Reception is a form of domesticity that is familiar to the East yet simultaneously foreign in its exotic decoration and costume. Both Lane and Lewis, who had each traveled to the Near East, omitted the expected eroticism of the harem in their works in favor of focusing on precise details of ‘direct’ observation which would verify the authenticity of their work.

In contrast to Lane’s literary propriety and Lewis’s visual domesticity, Burton’s translation of Arabian Nights was overtly sexual. In his commentaries, Burton openly discussed controversial subjects such as Sapphism and Tribadism (both of which are forms of lesbianism).[11] In one footnote, Burton even mentions his own personal experience of the harems during the campaign of 1857 in which “there was a formal outburst of the Harems; and even women of princely birth could not be kept out of the officer’s quarters.”[12] Through such comments, Burton reinforced European notions of the lascivious harem as well as the desirability of the white man for the exotic woman. The taboo nature of Burton’s account of Oriental eroticism is further evidenced by the fact that his translation was not widely published and its circulation was only among elite men. Even within a literary scope dominated by the Western translations of Arabian Nights, the eroticism of the Orient had already developed as a cultural site for male pleasure. Burton’s sensual portrayal of women in the Orient is parallel to the image depicted by Ingres in his painting Turkish Bath (1862). Unlike Burton, Ingres had never traveled to the Near East and thus utilized the eroticism found in literary sources like that of Burton for his portrayal of the harem. Turkish Bath conflates the then common European confusion of the harem as the Seraglio and simultaneously evokes the lesbianism referenced in Burton’s translation. In Turkish Bath, a plethora of nude women are crowded into the gendered space and are rendered exotic by their turbans and decadent by their jewelry, suggesting a scene from the Seraglio. Also, there is a suggestion of lesbianism through the close embrace of some of the women as a female figure caresses the breast of her companion to the right of the lute player. Thus, Ingres interiorized the Orientalism that pervaded his era because it allowed him to translate into images an intensity of desire that could declare itself only through the very remoteness of the subject.[13]

Although both Lane and Burton claimed validity for their additional commentary to Arabian Nights through their personal experience of travel to the Near East, their footnotes and commentaries still lack authenticity since both men remained cultural outsiders of the Orient and the harem/Seraglio. Thus, the reader of the Arabian Nights by either Lane or Burton as well as the viewer of Orientalist paintings, such as The Reception and Turkish Bath, receive a confusing mix of fact and fantasy.

In many of the represented harems, the pulls of fantasy and of fact are nearly inseparable.[14] One way the fantastical was buttressed with the seemingly factual was through the reliance on the travel writing of a Westerner’s personal experience of the Orient. Although Europeans craved authenticating details of harem life, it did not mean that they were necessarily in a position to recognize the truth when they saw it. The Western bias formulated by Oriental tales is reflected in the commentary provided in travel writings, especially concerning encounters with the harem. Since certain women could access the harem, their written description was seen as experientially authentic, and by the late 1840’s, a visit to the harem had become a regular item on the female tourist itinerary.[15] One of the first women during the 18th century to record her visit to the harem was Lady Mary Wortley Montagu. Lady Mary Montagu’s Turkish Embassy Letters (1717) served as a factual basis for many an artist in his depiction of the harem such as the famous Turkish Bath by Ingres. As an Ambassador’s wife, Lady Montagu had gained access to the Turkish harem, a forbidden place for men. However, despite Lady Montagu’s successful entrance into the harem, her written description of the unique event is clearly colored by her previous knowledge of Oriental literature. In one of her letters about Turkish baths, Lady Montagu commented, “so many fine women naked in different postures, some in conversation, some working, others drinking coffee or sherbet, and many negligently lying on their cushions while their slaves (generally pretty girls of seventeen or eighteen) were employed in braiding their hair in several pretty manners.” [16] Similar to the translations of Arabian Nights, Lady Monatgu’s writings involve the projections of a Westerner’s psyche. Lady Montagu inflected her own judgement of the exotic woman in her description of and idle women reclining with slaves preening them. Lady Montagu viewed the Turkish bath as a place which provided more freedom for women than a European home could provide, and thus she introduced her own Western fantasy of a female desire for lingering and relaxed companionship. Lady Montagu, like many women travel writers, persistently dismissed the more lurid masculine fantasies of the harem in describing it as solely a domestic space with exotic flavor; nonetheless, these women travelers continued to invest in the harem as a place of mystery and sexual intrigue creating a feminine version of the ‘imaginary Orient.’ [17] While women writers may have described the Turkish harems as extremely sensual in comparison to the European parlor, they were not objective or learned observers of the Muslim household, and consequently writings such as those of Lady Montagu should be treated as speculative rather than as generalizations of the whole Orient.

During the nineteenth century, few European women went into Muslim households, and even fewer European men had any experience with an actual harem or the much desired Seraglio. Thus, Westerners were more likely to rely on the romantic writers’ vision of the Orient for their voyeuristic travels. The narratives of both William Beckford’s Vathek and Thomas Moore’s Lallah Rookh epitomize the influence of Orientalism in prose. It is important to note that the tales of Vathek and Lalla Rookh are part of the Romanticism movement that was occurring in Europe. Romanticism was associated with the freedom of the imagination in which writers and artists appealed directly to the emotions of their audience.[18] One characteristic of the Romantic movement that was particularly well-suited for Orientalist tales was its element of escapism, making the exotic harem an appealing site for Romantic flights of fantasy. Both Beckford and Moore clearly portrayed the well-established myth surrounding the harem/Seraglio as place of pleasure and sexuality. Published in 1786, Vathek, named after the caliph protagonist, is an adventurous tale of a man who prioritizes his own pleasure over humanity. Based on several episodes of the Arabian Nights, Beckford characterizes Oriental decadence in the description of the palace in which each wing was dedicated to satisfying each of the senses: “The Retreat of Mirth, was frequented by troops of young females beautiful as the Houris, and no less seducing.”[19] A whole wing of women for male pleasure evokes an exaggerated version of the Seraglio. The novel with its anti-hero and exotic setting was extremely popular among the Romantics due to its glorification of the sublime and sensuality. During the nineteenth century, Moore’s creation of Lalla Rookh reflected the continuing popularity of the Orient as a sight for fantasy and adventure. Moore created a miniature of Arabian Nights in his poem in which the princess Lallah Rookh journeys to the kingdom of her future husband. On the way, Lallah Rookh falls in love with a young poet named Feramorz who recites four tales about lovers. In the last tale, titled “The Light of the Harem,” Moore evokes the seclusion and mystery of the harem:

Hence, is it too that Nourmahal,

Amid the luxuries of this hour,

Far from the joyous festival,

Sit in her own sequestered bower;

With no one near to soothe or aid,

But the inspir’d and wond’rous maid

Namouna, the Enchantress[20]

Here, the heroine of this tale uses the magic spell cast by the Enchantress to reunite with her lover. Once again, the conventional European notion of the harem as a place of seclusion and mystique is reinforced. Both Beckford and Moore lyrically describe the beauty of the harem adding to the sense of fantasy. With Orientalists creating their own poetry and prose to describe the harem, reality had truly become far-removed and the harem had been amplified into the Seraglio while Muslim women were replaced with fictitious seductresses, evoking the taboo of the West rather than the tradition of the East.

By examining the contrasting notions of the real harem and the represented Seraglio in the context of social reality and of literary fantasy, the foundation of the Oriental setting in Western paintings of the female quarters of the Muslim household is revealed to be a conflation of the harem and the Seraglio. The folkloric tales of Arabian Nights played a significant role in construing the harem as an eroticized space through its Arabic origin and subsequent interpretation. Although the sexualization of the harem may be rooted in Eastern tradition as evidenced in Arabian Nights, its additional exoticism was a Western contribution. The factual basis for this conflation of the harem and the Seraglio is aided by the writings of those who traveled to the Far East whether in their translations of Arabic tales or the chronicles of their own personal experience. However, since such writings did not make a distinction between the harem and the Seraglio for its reader, the gap between reality and fantasy widened creating a further disjunction between the actual harem of the Orient and represented harem of the Orientalist. With such a strong literary background as the main foundation of Orientalism, the imaginary harem was well-suited to relocate into another medium - oil on canvas.

DISORIENTED IN THE HAREM WILL CONTINUE IN THE NEXT POST

"PART III: VISUAL ACCESS TO THE HAREM SPACE"

Enjoyed reading? Subscribe to our newsletter.

Ahlstrom Appraisals | Personal Property Appraisals and Art Consultations | Serving Atlanta & Southeast | Fine Art, Antiques & Vintage

[1] Dictionary.com Unabridged (v 1.1). Random House, Inc. http://dictionary.reference.com/browse/citation (accessed: March 10 2009).

[2] Ruth Yeazell, Harems of the Mind: Passage of Western Art and Literature (Haven: Yale University Press, 2000), 1.

[3] Ibid., 1.

[4] Raan Kabbani Imperial Fictions: Europe’s Myths of Orient (London: Saki, 2008), 42.

[5] Ruth Yeazell, Harems of the Mind: Passage of Western Art and Literature (Haven: Yale University Press, 2000), 45.

[6] Shirly Foster, “Colonialism and Gender in the East: Representations of the Harem in the Writings of Women Travellers,” The Yearbook of English Studies 34 (2004): 7.

[7] Raan Kabbani Imperial Fictions: Europe’s Myths of Orient (London: Saki, 2008), 49.

[8] Powys Mathers, Arabian love tales: being romances drawn from the Book of the thousand nights and one night / rendered into English from the literal French translation of J. C. Mardrus (London: Folio Society, 1949), 17.

[9] Nicholas Tromans, ed., The Lure of the East: British Orientalist Painting (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2008), 14.

[10] Lane’s negative stereotyping of the Eastern woman is also exemplified in his work Manners and Customs of Modern Egyptians in which he comments on the personality of the Egyptian women: “Most of them are not considered safe unless under lock and key…It is believed they possess a degree of cunning and management of their intrigue which the most prudent and careful of husbands cannot guard against…” (London, 1836), 296.

[11] Burton’s discussion of lesbianism in the Orient is especially evident in his commentary on the harems of Syria: “Wealthy harems, as I have said, are hot-beds of Sapphism and Tribadism. Every woman past her first youth has a girl whom she calls her ‘Myrtle.’ A Plain and Literal Translation of the Arabian Nights’ Entertainment, now entituled The Book of Thousand and One Nights (London, 1886), 234.

[12] Ibid., 13.

[13] Gerard-Georges Lemaire, The Orient in Western Art (Cologne: Könemann, 2005), 202.

[14] Ruth Yeazell, Harems of the Mind: Passage of Western Art and Literature (Haven: Yale University Press, 2000), 31.

[15] Shirley Foster, “Colonialism and Gender in the East: Representations of the Harem in the Writings of Women Travellers,” The Yearbook of English Studies 34 (2004): 8.

[16] Letters of the Right Honourable Lady Mary Wortley Montagu: written during her travels in Europe, (Eighteenth Century Collections Online: Berlin, 1790).

[17] Mary Roberts, Orientalism’s Interlocutors (Durham: Duke University Press, 2002) 181.

[18] David Brown, Romanticism (New York: Phaidon Press Limited, 2001), 5.

[19] Vathek (London, 1970), 2.

[20] Lalla Rookh An Original Romance (London, 1814), 158.