Part IV: The Male Voyeur in the Imagined Harem

Within the tradition of Orientalist paintings, the imagined harem was often represented in two modes: the domestic and the erotic. These two types of portrayals of the feminine Muslim space are partially rooted in the cultural discourse of the Near East, such as the Arabian Nights, which was then expanded upon by eighteenth and nineteenth century Orientalists who also incorporated Western perceptions of the ideal woman and the environment in which she inhabited into their representations of the harem. The role of the ideal woman included a particular moral significance since she was believed to be the guardian of the private sphere and was crucial to creating domestic order.[1] Also, with the separation of the male public sphere (i.e. the workplace) from the female private sphere (i.e. the home), the bourgeois home was emptied of its association with work and became defined instead around notions of leisure.[2] Both the concept of the ideal woman and the relaxed nature of the home pervaded Orientalists’ interpretations of the harem in which these features became exotic and exaggerated. Similar to Orientalist writings, the represented harem signified less of the real circumstances of the Oriental woman and more of the fantasies of the Occidental man. Whether domestic or erotic, the Orientalist harem reflected a European construction of the ideal woman in the home set within a non-Western space, allowing the male viewer to imagine a far away place where such images might actually exist. Some artists, such as John Frederick Lewis, injected the West’s domestic ideology into the representation of the harem. Yet other painters, such as Ingres, stressed the leisurely associations of the women at home in his portrayal of the harem laced with sexual decadence. In examining the contrasting depictions of the harem by Lewis and Ingres as domestic and erotic, the patriarchal values of women’s social role in nineteenth century Europe are discovered to be visually relocated into the Orientalist landscape.

Lewis applied the notion of the good Christian wife to that of the good Muslim wife. A popular phrase for the sort of ideal wife that was to be found in England was the ‘Angel in the House,’ originally the title of one of Conventry Patmore’s poem (1856). [3] This concept of the ‘Angel in the House’ pervaded much of Western European, helping the middle classes define family values. [4] Since the English middle class desired paintings that contained moral narratives featuring ‘real’ subjects, [5] Lewis’s construction of the harem scene fitted appropriately into the visual viewing that was popular at the time. Lewis provided an apparent ‘window of reality’ for the western viewer in which the visual story was filled with anecdotes that could be easily understood without having an understanding of Oriental culture. For instance, in The Reception, a social gathering of women is taking place in the harem that appears similar to the Western social customs of ‘paying calls’ and ‘taking tea.’ In The Reception, the Ottoman women are lined up waiting their turn to be formally greeted by their hostess whose social importance is highlighted by being the sole figure to lounge in a room filled with plenty of sitting areas. Although the painting is distinguished from a national vignette through its exotic setting and Oriental dress, there is nevertheless a marked similarity between the Victorian middle class and the Ottoman upper class since both cultures defined gender boundaries with women’s activities being confined mainly to the private sphere of the home. [6] By creating visual parallels between the European and Oriental home, the Other (upper class Muslim lady) became like the Victorian woman as both identities were interlinked with the welfare of the home. Lewis’s idealization of female domesticity was nothing new to the Victorians. However, by situating the scene of the feminine hearth in a harem, Lewis provided an alternative approach to the ‘good woman’ who became both domestic and Other. Thus, the Western desire to understand the Orient is fulfilled by Lewis’s image in which the mysterious world of the harem is fashioned into a more familiar sight for his Victorian audience.

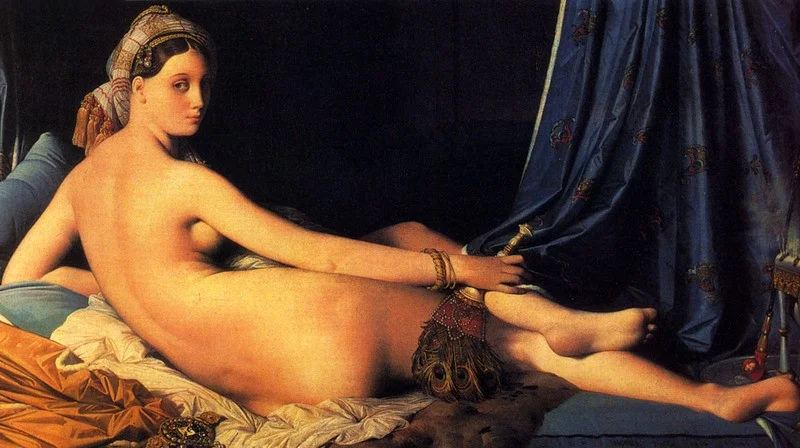

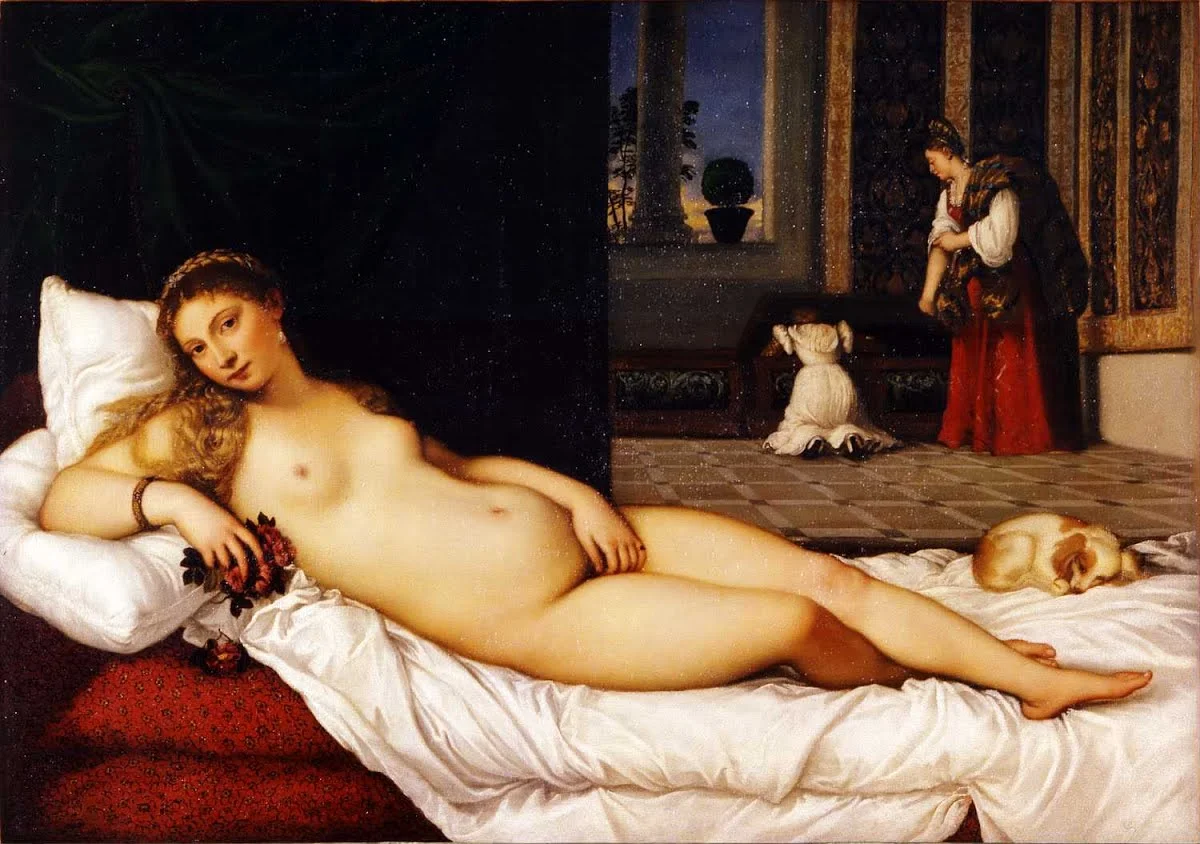

In contrast to Lewis, Ingres eroticizes the leisurely atmosphere of the harem making it distinct from the Western home. Similar to Burton’s commentary in Arabian Nights, Ingres’s Turkish Bath suggests the harem as a place of sexual transgression. Unlike Lewis’s attempt to parallel the social gatherings of Oriental women to those of European ladies, Ingres emphasizes difference in communal behavior between West and East. Instead of a domestic scene, Ingres’s Oriental women seem enveloped in an atmosphere of orgy as the multitude of female figures lounge in the nude. One historian’s description of Turkish Bath as “an erotic daydream of an elderly painter”[7] conveys the sentiment that Ingres’s vision of the harem is a subjective male fantasy rather than an attempt to capture the ‘real’ harem. Although superficially inspired by Lady Montagu’s Turkish Letters, Ingres has clearly embellished the scene to include an array of sensual delights as indicated in the painting’s catalogue description in which “to the accompaniment of mandolin and tambourine, hair is perfumed, incense is burned, sweets and coffee are consumed, flesh is caressed, and bodies are relaxed in pagan abandon.” [8] While the exotic context of the scene is grounded in Orientalist writings, the image of a nude woman clearly references Western painting tradition such as Titian’s Venus of Urbino (1538). However, instead of using mythology as a respectable means to portray the female nude, Ingres employs the Orient as a context for portraying the erotic without receiving public disapproval. Similar to mythology, the Orient was a removed setting that was outside Western society and thus provided artists a means to distance the taboo subject of the nude making it into a less controversial depiction. Thus, Titian’s lone goddess has been multiplied into more than twenty Muslim women. In fact, the exaggerated number of women in Turkish Bath suggests that Ingres’s vision is more closely aligned with the Seraglio than to the more common harem. Another way in which the Turkish Bath could be viewed is as a variant of the slave-market theme[9] in which the women are herded together as they preen themselves in preparation of the Sultan. Unlike mythological paintings, Orientalist paintings provided a fantasy that was closer to reality since harems actually did exist even if the women inside were, in truth, clothed. Through an Oriental setting, the erotic charge of the nude was both subdued and reinvigorated since the exotic locale distanced the subject while the actual existence of the harem provided a sensual immediacy that was desired by the male viewer. Harem scenes attracted Ingres no only because of their exoticism and the opportunities these scenes provided for presenting the female nude in a convincing setting but because they enabled him to show women as playthings, victims of male caprice.[10] Thus, women’s privilege of leisure for the woman at home becomes subverted by Ingres since in his depicted harem, women are limited to their gendered space and are at the disposal of male pleasure. Besides exaggerating the leisure of the harem through heightened sensualism, another way in which Ingres’s interpretation of the harem is eroticized is through his distortion of the figure of the Oriental woman. In Grand Odalisque (1814, see Figure 8), the harem setting seems almost credible through Ingres’s’ technique of glassy objectivity in depicting the accouterments: the pipe and smoking censer, the peacock feather, the pearl buckle of the discarded belt, the floral patterns on the blue curtains, the wrinkles of the sheets, the gold tassels on the turban.[11] Yet, the anatomy of the odalisque is clearly based on the imagination as her elongated back includes three extra vertebrae. Along with the distorted proportions of the subject, the model used by Ingres, like almost all of those used by Orientalist painters, was a European. In this instance, the model is even more distant from an actual harem woman since she was a young girl as evidenced in Ingres’s letter to the Ambassador of Naples: “…my model is in Rome, it’s a 10 year old girl...” [12] However, it is this unrealistic interpretation of the Oriental woman which heightens the aesthetic eroticism of the work. Unlike Lewis, whose aim was to suggest the domestic ideal through realistic detail, Ingres’s idealized harem image was to be openly fantastical and clearly in opposition to the European woman.

In Ingres’s harem scenes, it is the viewer’s power of the omniscient gaze over the subject that allows for the male fantasy. Since Muslim women were culturally hidden from the male gaze, the ability to view the harem was limited to its represented version. Despite the clearly western perception that is expressed in these Orientalist paintings, the role of the viewer in Ingres’s harem scenes is strangely ambiguous. While the viewer may be left to question what role to imagine, what is made clear is that the intended viewpoint is that of a male voyeur. In fact, the ‘communication’ of these paintings relies on the shared psychic formation premised on the fact that sultan, artist, and viewer are male. [13] For instance, although Ingres’s Turkish Bath does not aim for an accurate representation of the harem, it does provide a pictorialization of the act of voyeurism through the work’s round shape. The illicit quality of peering into a space forbidden to men is conveyed through the keyhole shape of the painting, implying that the viewer is a Peeping Tom. Another way in Ingres suggests the rarity of a glimpse into the harem can be seen in Grand Odalisque in which the pulled back blue curtain indicates that the viewer is privileged to see what would otherwise be screened from his view.[14] In contrast to the viewer’s gaze being unknown to the subject in Turkish Bath, the subject of Grand Odalisque gazes directly at the viewer acknowledging his presence. Thus, the voyeur is asked to entertain a harem fantasy: that of a man entering the harem unimpeded and being welcomed by a beautiful odalisque. [15]

However, since Caroline Murat commissioned Grand Odalisque, the engagement of female spectatorship and “feminine” taste complicates assumptions made about pleasure and power[16] in Orientalist paintings of the harem. Despite its female patronage, Ingres’s odalisque painting was most likely intended as a gift for Murat, King of Naples.[17] Thus the confusion of gender binarism associated with Orientalism occurs not only within the content of the painting but also in its patronage. Caroline Murat’s patronage is unlike the female artist Henriette Browne’s depiction of the harem as a humble domestic space which was in great contrast to the representations of the harem created by her male counterparts. Instead, Caroline Murat commissioned a work which was in keeping with the exotic and erotic traditions of the imagined harem, perhaps because its intended viewer was her husband.[18] Thus, when considering the influence of Orientalism on harem paintings, it is incorrect to assume that its framework relies on clear gender oppositions between male and female. As exemplified by the female patronage of Grand Odalisque, the roles of the male voyeur and the submissive female subject may exist within the fantasy of the Orientalist painting, but necessarily within the social context of the West. Despite the issues of gender surrounding the creation of Grand Odalisque, its idealized representation of the harem woman continued in the Orientalist convention of grounding its depiction on patriarchal aesthetics of the West and not on Oriental reality.

Conclusion

In attempting to locate the disoriented harem, an understanding of the Orientalist imagination is needed, in which the conflict between the real and represented harem resulted in an Occidental fantasy with little grounding in Oriental reality. This imaginary harem, which can be found in the literature and paintings of the West from the 18th and 19th centuries, relied heavily on the exotic world found in Arabian Nights as well as on the writings of those Westerners who had traveled to the Near East. Because of the limited access to the harem and the appropriation of Oriental fiction as fact, the Orientalists often conflated the harem with the Seraglio in order to highlight the space’s erotic potential. Depending on how artists idealized their depiction of the harem, it affected the viewer’s interpretation of the Oriental woman who could be seen as either foreign or familiar, domestic or erotic, accessible or forbidden. Thus, the harem depicted in 19th century paintings is and always has been the only visible landscape of this particular Orientalist fantasy.

Enjoyed reading? Subscribe to our newsletter.

Ahlstrom Appraisals | Personal Property Appraisals and Art Consultations | Serving Atlanta & Southeast | Fine Art, Antiques & Vintage

[1] Lynda Nead, Myths of Sexuality: Representations of Women in Victorian Britain (Oxford: Basil Blackwell Ltd, 1990), 24.

[2] Ibid., 32.

[3] Rachel Fuchs and Victoria Thompson, Women in Nineteenth Century Europe (Macmillan: Palgrave, 2005), 35.

[4]Ibid., 35.

[5] Caroline Williams, “John Frederick Lewis: Reflections of Reality,” Mugernas 18 (2001): 231.

[6] Ibid., 231.

[7] Robert Rosenblum, Ingres (New York: Harry N. Abrams,1990), 126.

[8] Ibid., 128.

[9] Edward Lucie-Smith. Sexuality in Western Art (London: Thames and Hudson Ltd., 1997), 180.

[10] E Lucie Smith. Sexuality in Western Art, London: Thames and Hudson Ltd., 1997. 118

[11] Robert Rosenblum, Ingres (New York: Harry N. Abrams,1990), 126.

[12] Carol Ockman, Ingres’s Eroticized Bodies: Retracing the Serpentine Line (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1995), 36.

[13] Ibid., 37.

[14] Ruth Yeazell, Harems of the Mind: Passage of Western Art and Literature (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2000), 27.

[15] Ivan Kalmar, “The Houkah in the Harem: On Smoking and Orientalist Art,” in Smoke (Chicago, Reaktion Books, 2004), 222.

[16] Carol Ockman, Ingres’s Eroticized Bodies: Retracing the Serpentine Line (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1995), 33.

[17] Ibid., 35.

[18] Not only was Caroline Murat driven by her husband’s tastes, her patronage of Grand Odalisque was also in response to Canova’s sculpture Pauline Bonaparte (1808) in which the patron and suggested model was Caroline’s sister, Pauline. Thus, Pauline Bonaparte’s sculpture provides the frontal view of the erotic woman while Caroline’s painting provides the view of the back. Carol Ockman, Ingres’s Eroticized Bodies: Retracing the Serpentine Line (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1995), 36.