Part I: Investigating the Orientalist’s Imagination

Introduction

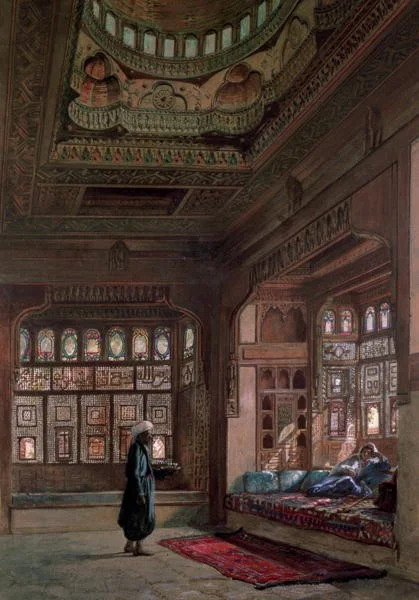

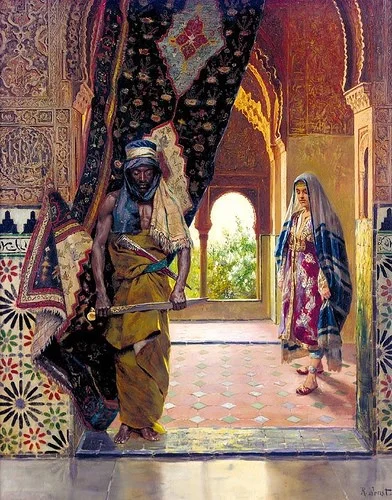

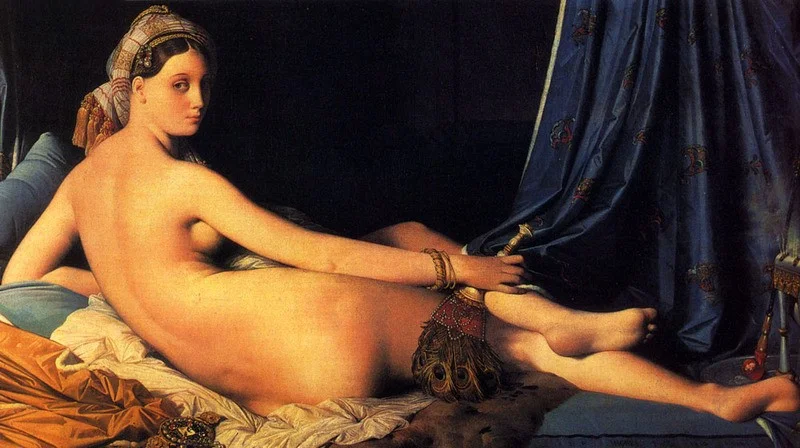

Culturally speaking, can the Orient be truly described as a place found in the Near East? Even today, when the notion of the Orient is conjured up in the Western mind, what is often found is not an objective perception of the various nations and cultures existing beyond the borders of Europe, but rather an idealized vision of the East as an exotic Other, the foil to all things Western. Thus, what is traditionally associated with the Orient is really a disorientation, that is the dislocation of the actual place of the Near East through Western culture into an imagined geography. Such latent misconceptions of the Near East in the 21st century are rooted in 18th and 19th century Orientalism. At the height of imperialism, the tradition of orientating the Near East around the periphery of a Eurocentric culture manifested itself in Orientalist paintings. Orientalist painters rarely drew inspiration from personal experience of the East but rather relied heavily on literary sources where the myth of the Orient sustained itself with little help from reality. This landscape of fantasy is particularly revealed in the popular use of the harem space as a setting in which what was morally taboo in Western society becomes central to the visual construction of the Eastern woman.[1] To locate this disoriented harem, it is important to examine how the gendered space in a Muslim household was transformed into an illusory realm of fantasy which reflected the patriarchal values of Western bourgeois morality. Through a social art history approach, the crucial role that both text and image had in constructing the Western view of the harem will be examined. In particular, the Western confusion between the real and represented harem will be explored in which the imagined harem of the Orientalists more often resembled the erotic quarters of the Ottoman palace (known as the Seraglio) instead of the domestic space of the traditional Muslim home. In contradiction to the artists’ implication that their image of the harem embodies Oriental femininity, a contemporary viewer is more likely to see a reflection of Occidental masculinity.

Before investigating the Orientalist’s imagination through visual means, scholarship regarding the term ‘Orientalism’ must be discussed in order to situate the cultural context of the represented harem. One of the most influential academic voices in defining Orientalism is Edward Said. In his 1975 work Orientalism, Said defines the Orient as a system of representations framed by political forces that brought the Orient into Western learning in which the Orient has been constructed to be the mirror image of what is alien or Other to the West. Thus, Orientalism is part of an accepted grid for filtering the Orient into the Western consciousness and “an integral part of European material civilization and culture.”[2]

There are a range of terms used to analyse Orientalism in which ‘Orient’ is the root, and consequently it is important to define these terms as used in this essay. The ‘Orient’ is the physical location of the Near East which has been generalized without political boundaries and with no clear distinction between cultures, races, and nations. Those who inhabit the Orient are the Orientals. The term ‘Oriental’ is used to describe a person native to the Orient, such as the Muslim woman. In contrast, an ‘Orientalist’ is a person who is an outsider to the Orient yet is invested in defining its culture. The most common Orientalist, especially during the 18th and 19th century, was a European male who had traveled to the Orient and recorded his experience. Another more specific type of Orientalist is the Armchair Orientalist[3] which is someone who contributed to defining Orientalism yet had never been to the Near East. Thus, the Orient and the Oriental are closely linked constituting the social formation of the Near East while Orientalism and the Orientalist are related to Western culture since they comprise the cultural discourse surrounding the Near East. Even within the terms used to describe Orientalism, the polarities of the East and West are present. However, the West’s reconstruction of the harem as an erotic space is an elaboration of what was already culturally established in the Near East as will be later demonstrated by the influential text Arabian Nights.

According to Said, the first Orientalists were 19th century scholars who translated the writings of the East into English. Since Orientalist discourse was essentially male and based on an East/West oppositional relationship, the ‘power of domination’ became an essential feature to govern a battery of desires and repressions and thus expressing a certain intention to understand, and in some case to control, what is manifestly different.[4] This necessity of domination can be seen in the Orientalist belief that Eastern women were eager to be dominated. Such explanation of femininity as being passive is applied not only to women but also to the Orient itself. By describing the Orient as a feminine culture, sexuality was used to signify what is both desired and feared in the Western (male) imagination.[5] Said argued that the Orient was viewed by Europe to be a sort of surrogate, underground version of the West which was backward, passive, feminine, and sexually corrupt. Thus, the Oriental paradigm becomes a useful ideological instrument for imperialism in which the domination by the West becomes justifiable.

Another cultural critic who discusses the theory of Orientalism is Ziauddin Sardar who emphasizes its effect upon the Western psyche. Sardar states that Orientalism’s greatest potency is its aesthetic power within the Western mind.[6] The original site of Orientalism, according to Sardar, was Islam in which the West’s encounter of a non-Christian place provided a vision of the unfathomable and the erotic. For the Western gaze, the Orient provides exotic and sexual delights wrapped in an ancient and mysterious tradition.[7] Crucial to creating this atmosphere of primordial mystery is the view of the Orient as a place of timelessness which is situated outside the chronological framework of Western societal development. While the West progresses and changes, the Orient remains unchanged and hence remains culturally backwards. Thus, the Orient came to signify that which the West both oppressed and desired, i.e. eroticism. Sardar argues that Orientalism serves both the external collective desire to possess the Orient and the internal desire to appropriate it.[8] Thus, the paintings of harem women as the object of the viewer’s gaze are the ultimate representations of the Orient.

When discussing the Orientalism of the 18th and 19th century, the position of an academic Oriental (such as Said and Sardar) is a recent development of the 20th century. What was more prevalent in Orientalism scholarship was a 20th century Orientalist commenting on previous Orientalist scholarship such as art historian Christine Peltre. Peltre describes the Orient as a land of fable, of “pure poetry” where nothing has weight.[9] Consistent with the criticisms of Said and Sardar, Peltre viewed the Orient as an enchanted elsewhere. Peltre specifically focuses on the Orient as a conceptual place of pure frivolity which was to be encountered in literature and painting almost like a theatre set for the artist. [10] Like many Orientalist of the 20th century, Peltre emphasizes the concept of the Orient rather than the discourse surrounding it.

Although Said, Sardar, and Peltre are recognized for their reputable analyses of Orientalism, their use of the polarity between East and West in relation to eroticism is ill-founded when it comes to the harem. Rather than viewing the eroticized harem as a purely Western construction, it would be more accurate to consider the sexualizing of the female space as present in both Eastern and Western tradition creating an overlap in the notion of the harem as a site for male pleasure. What may be more arguable is the Western amplification of the harem into the Seraglio and the projection of exoticism onto the foreign space. Rather than further examining the writings of Oriental and Orientalist academics of the 20th century, it is more useful to look at the Orientalist literary sources which influenced 19th century paintings of the harem as an exotic Seraglio.

Disoriented in the Harem will continue in the next post

"Part II: Location the Real Harem, the Literary Seraglio"

Enjoyed reading? Subscribe to our newsletter.

Ahlstrom Appraisals | Personal Property Appraisals and Art Consultations | Serving Atlanta & Southeast | Fine Art, Antiques & Vintage

[1] Stallybrass and White discussed the concept of the Other which becomes culturally centered in The Politics and Poetics of Transgression. In this essay, the Oriental woman will be examined in relation to its depiction as a centralized Other in 19th century painting. (London: Methuen and Co. Ltd, 1986), 3.

[2] Alexander Macfie, Orientalism, (London: Pearson Education Limited, 2002), 9.

[3] Christine Peltre, Orientalism in Art (New York: Abbeville Press, 1998), 183.

[4] Edward Said. Orientalism (New York: Pantheon Books, 1978), 5, 8,12.

[5] Shirley Foster, “Colonialism and Gender in the East: Representations of the Harem in the Writings of Women Travellers,” The Yearbook of English Studies34, (2004): 6.

[6] Orientalism (Buckingham: Open University Press, 1999), 11.

[7] Ibid., 5, 7.

[8] Ibid., 2.

[9] Orientalism in Art (New York: Abbeville Press, 1998), 9.

[10] Ibid., 9.