Innovation through Traditional, Exotic, and Industrial Materials

French Seating Furniture (1920’s-1930’s)

A “seat” is defined as an object designed to support a person in the sitting/reclining position. By the end of the nineteenth century in France, a standard had evolved for seating furniture to be typically made of wood and textile upholstery. Yet with the dawn of the twentieth century, designers began to challenge the assumption of what could be the composition of a “seat.” Modern life, with all of its innovations in technology and increasing interactions on a global scale, brought unprecedented material options for designer experimentation. This transformation is especially evident in seating furniture by French designers during the interwar period, which became stylistically became known as Art Deco or Moderne. In examining the different materials used for seating furniture in the 1920’s and 1930’s, certain themes are revealed including: the upholding of traditional skills, the adoption of exotic materials and techniques, and the adaptation of industrial products. Through the innovative use of materials by Moderne designers, the range of seating furniture available in France evoked modernity through a multi-sensory experience.

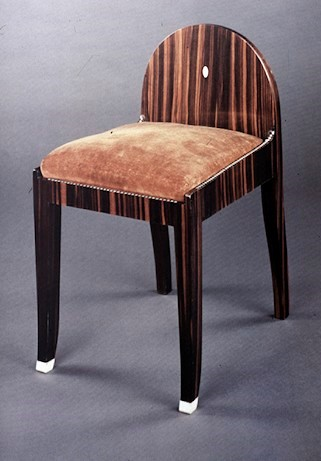

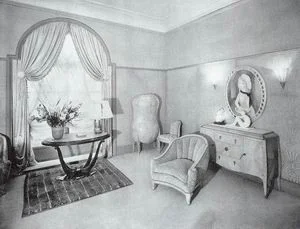

Although more unorthodox materials were employed for seating furniture during the interwar years in France, wood continued to be used as exemplified by the designs of Jacques Ruhlmann. Ruhlmann’s work was of superior quality comparable to the pieces created by eighteenth-century furniture makers. [i] However, unlike the French ébénistes of the past, Rulhmann was the designer and not the maker of his furniture. Nevertheless, his artistic direction is manifested in the way the materials were manipulated for his pieces. For example, Ruhlmann designed a bedroom interior, which included a dressing table with an accompanying Dressing Table Chair as evidenced in the photograph. The Dressing Table Chair. has the hallmark traits of Ruhlmann’s furniture through its use of macassar ebony and ivory inlay. Ruhlmann was especially fond of integrating macassar ebony with ivory ornamentation in order to create an appealing contrast between the dark striations of the wood grain and the stark white of the ivory. Improvements in glue in the twentieth century facilitated more challenging inlay designs such as ivory on wood. Macassar ebony and ivory not only connoted luxury through its sensory appeal and also because it was exotic. Both of these materials were imported from France’s colonies with the macassar ebony coming from the Ile de Celebes in Indonesia and the ivory from Africa.[ii] Further, the use of such exotic materials imported from the French colonies was a subtle indication of France’s continued imperial influence before World War II. The Art Deco historian Alastair Duncan argues that ivory replaced ormolu as the period’s foremost furniture mount[iii] as demonstrated by the ivory sabots on the front legs of the Dressing Table Chair. Through small details such as ivory volute pattern around the seat lent a sense of refinement, allowing Ruhlmann to achieve his desire to makes his pieces like this chair “precious.”[iv] While this low back chair is not innovative in form, the exotic materials used mark it as a chair of the twentieth century.

Another piece of seating furniture whose materials evoke luxury is Eileen Gray’s lacquer furniture. Gray never formally trained as a furniture maker but rather specialized in lacquer. Lacquer is made from the resin of a tree found in Asia. Originally developed in China and Japan, lacquer is a labor-intensive process in several coatings are applied to an object creating a smooth surface that is waterproof and its color never fading.[v] Lacquer had been greatly admired by Europeans in the late seventeenth and early eighteenth century; however, Europeans were unable to successfully reproduce lacquer and instead in attempt to mimic the appearance of lacquer, invented japanning through the application of several coatings of black varnish,. It was not until the twentieth century that lacquer was produced in Europe, and it was initially used to waterproof plane propellers during World War I.[vi] With the end of the war and loss of employment, lacquer technicians began using their skills in the decorative arts. At this time, Gray became interested in the process and learned the technique of lacquering from the Japanese master Sugawara, [vii] who also trained another famous lacquer artist, Jean Dunand. Thus, lacquer was a material that was exotic in origin, costly to make, and even in a sense industrial since its appearance in Europe began in aviation.

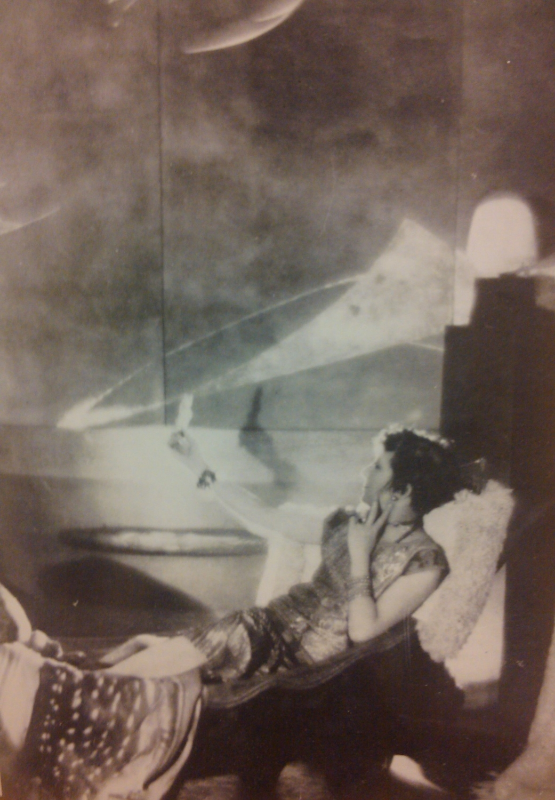

An example of Gray’s use of lacquer for a luxurious interior is the chaise longue for Suzanne Talbot known as the “Pirogue” Sofa.[viii] In 1919, Gray received her first commission as an interior designer from Suzanne Talbot, who was a successful modiste in Paris. Gray was hired to furnish the entire space of the apartment from the lighting fixtures and carpets to the lacquer walls.[ix] Both the patinated brown exterior and silver leaf interior of the “Pirogue” Sofa echoed other lacquer objects that were placed in the apartment, including the lacquer screen which appears behind the sofa in a 1920 photograph. To achieve the silver leaf lacquer on the interior of the sofa, silver was sprinkled onto wet lacquer for several layers with the last coat of silver leaf being burnished.[x] Such a combination of lacquer and silver heightened the sense of opulence. Also, both the form and medium of the “Pirogue” Sofa was influenced by the exotic; its shape is derived from a Polynesian or Micronesian dugout canoe while the lacquer that covers the structure is an Oriental technique.[xi] Through combining the exotic and the lavish in the materials and form of the “Pirogue” Sofa, Gray provided a type of seating furniture, which complemented the deluxe interior of Talbot’s apartment.

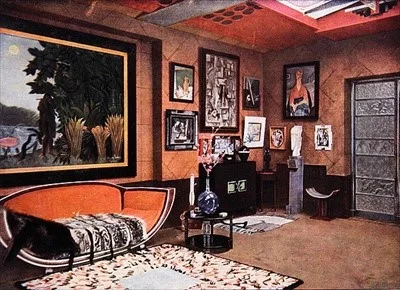

This combination of primitivism and luxury through materials can also be seen in the furniture designed by Pierre Legrain for Jacques Doucet. Doucet was a prominent Parisian couturier and collector who had dramatically shifted his taste from the eighteenth century to contemporary. Doucet commissioned several avant-garde designers to create furniture for his newly decorated villa in Neuilly. [xii] Among these designers was Legrain, who had previously worked on book-bindings for Doucet and who was put in charge of the main schemes of the interiors in 1925. The main theme of Neuilly studio was Africa, and in this room, artifacts, modern art, and furniture loosely based on tribal designs were displayed. Legrain also designed furniture that was inspired by African models such as the Stool. The shape of the Stool emulated those that were made by the Ngombe tribe in what is now the Democratic Republic of the Congo. While the overall shape of Legrain’s Stool is similar to the African example, especially with its curved backrest, the materials applied to it indicate its French origin. Instead of covering the wood carcass in metal tacks as was commonly done to the Ngombe stools, Legrain covered the surface with a deep red lacquer and gilt decoration. The use of lacquer and gilt paralleled Gray’s surface treatment of the “Pirogue” Sofa. And like the “Pirogue” Sofa, the Stool is a reinvention of a functional form into a decorative object: [xiii] the canoe turned sofa and the stool turn “primitive” accessory. Legrain even incorporated the more rustic material of horn for the legs, which can be compared to Ruhlmann’s refined addition of ivory sabots.

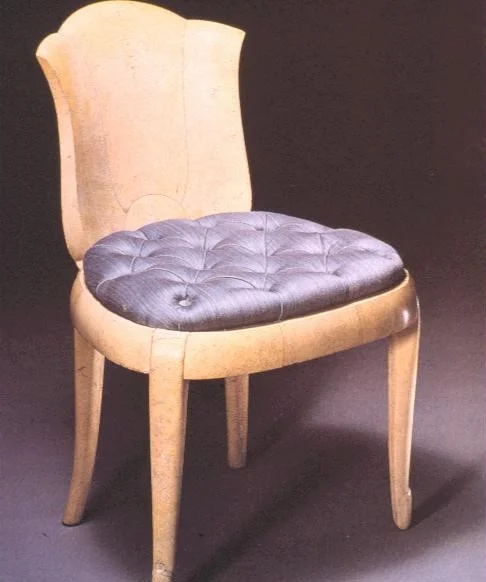

Another sumptuous material that was popular during the Art Deco period was shagreen. Shagreen is a type of leather made of either the skin of a shark or a stingray, and its texture is very granulated. Although naturally creamy, shagreen can be dyed any color, and the grain is often polished so that the hard nodules contrast with the dyed leather. [xiv] Like lacquer, shagreen was also popular during the eighteenth century in France and was adopted from Asia to cover small containers.[xv] And like ivory, shagreen was glued into position onto the wood carcass. During the interwar period, shagreen experienced a revival in France in by which designers such as André Groult who designed large scale objects covered in shagreen, which was executed by the craftsman Chanaux, including the Chair made for the “Chambre de Madame” in the Ambassade Francaise at the 1925 Exposition. As a member of the Societe de Artes Decoratifs (S.A.D.), Groult was commissioned to create a wife’s bedroom for the imaginary French embassy. As indicated by the sketch of the bedroom (fig.9) the interior achieved a feminine atmosphere through the use of pale tones, such as powdery pink, and through the use of soft rounded forms for the furnishings, which were accented with shagreen.[xvi] The Chair demonstrates the tone of Groult’s interior, in that it was simultaneously restrained and provocative. [xvii] At first impression, the Chair is not the most innovative, especially with the inclusion of a more traditional tufted seat. Yet, the tulip/lotus shape which forms the back of the chair refers to an Egyptian flower form and thus reflects the Egyptomania craze that was occurring with the discovery of Tutankhamun’s tomb in 1922.[xviii] In addition, Groult’s use of shagreen provided a sensual quality to the Chair and also unified the furniture within the bedroom by employing the same material throughout. Similar to macassar ebony and lacquer, shagreen was expensive and consequently its inclusion on any object indicated luxury.

While Groult and Ruhlmann were using unusual and costly materials -such as macassar ebony, ivory, or shagreen- for the seating furniture for the wealthy, there was a restraint on the overall structure of the chairs. An interesting comparison can be made between Groult’s Chair and Ruhlmann’s Dressing Table Chair. Both chairs are part of a costly suite of furniture intended for a bedroom for a wealthy woman. Neither Groult nor Ruhlmann designed innovative forms for their chairs but rather relied on the application of exotic and expensive materials to provide an updated appearance for the twentieth century. Such a combination of the established modes of production and the innovation of materials used by these designers can be described as “modernized tradition” in which artistic boundaries are pushed within the limits of more conventional forms.[xix]

In contrast to the seating furniture produced by Ruhlmann, Gray, and Groult for the elite consumer who could afford the price of exotic materials, other designers were considering the use of industrial materials in the hopes of mass-production. For example, the collaborators Le Corbusier, Charlotte Perriand, and Pierre Jeannert sought a means of creating affordable furniture through the use of tubular steel. While Ruhlman declared, “I have never even thought of mass-producing my furniture,” Le Corbusier’s team followed the Bauhaus mentality that everyone should have equal access to furniture.[xx] Le Corbusier, Perriand, and Jeannert exemplified the French avant-garde designers’ rejection of the furniture of the past in favor of rationalist design.[xxi] In fact, Le Corbusier believed, “It is possible to seat oneself in several ways, and the new shape of [the] chair must correspond to these different ways. By using metal tubing or sheet metal to construct the new seat shape, the problems disappear; the traditional use of wood hindered initiative.” With this functional attitude towards design, Le Corbusier replaced the word “furniture” with “equipment” and viewed the home as a living machine. This tension between more traditional and rational designers in France resulted in a split from the Société of Arts Dcoratifs (S.A.D.) and the formation of Union des Artistes Modernes (U.A.M.) in 1929. As a reaction to the elitist attitudes of S.A.D., members of the U.A.M., including Le Corbusier and Perriand, emphasized the social benefits of using industrial materials in furniture through its potential for mass production.[xxii]

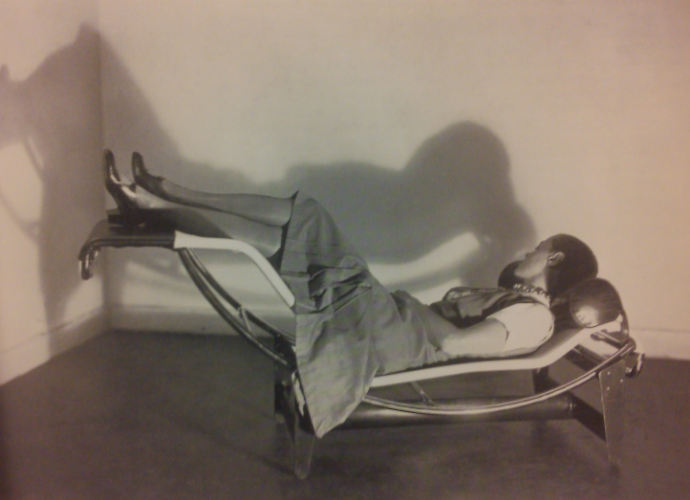

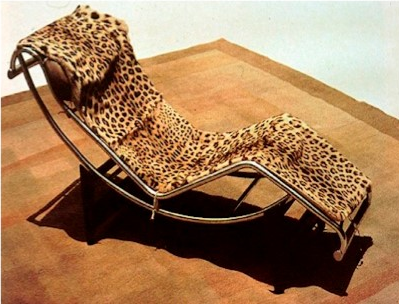

As demonstrated by the Chaise Longue, tubular steel was an ideal material for Le Corbusier, Perriand, and Jeanneret to represent modernity in furniture.[xxiii] Tubular steel was initially developed in 1885 by the German firm of Mannesmann, which perfected the technique of heating a billet that was pierced and then rolled into a tube; this form of steel was perfectly suited for bicycles. In fact, Le Corbusier’s team sought bicycle manufacturers to create the detachable metal support for the Chaise Longue. Le Corbusier even mentioned this industrial fabrication in his description: “We built it with bicycle-frame tubes and we covered it with magnificent pony skin; it is so light that it can be pushed with the foot, it can be moved by a child...”[xxiv] Since tubular steel was without tradition in the 1920’s, there were no associations with gender. When compared to the “feminine” chairs for a vanity designed by Ruhlmann and Groult, the Chaise Longue combined the male and female attributes traditionally given to furniture such strength and lightness.[xxv]

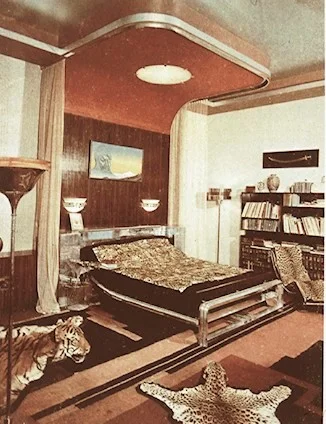

Another material that was used to create the Chaise Longue is the pony skin. The design of the Chaise Longue is attributed specifically to Charlotte Perriand, which may explain this choice of material for the covering. Reportedly, Perriand commented that her childhood memories of the Alps with her grandparents inspired her to consider folk furniture that was covered in animal skins.[xxvi] Although the initial prototype was covered, another Chaise Longue was made for the bedroom of the Maharaja of India. For this bedroom, the Chaise Longue was covered in leopard skin making it only a more like costly object similar to lacquer of the “Pirogue” Sofa; it also matched the other skins of big cat species that decorated the interior. The example of the Maharaja’s Chaise Longue also highlights the irony of Le Corbusier’s furniture: although multiples when it was first produced since were made and tubular steel was used, the Chaise Longue was not mass produced as was hoped.

René Herbst was another member of the UAM who was a pioneer in employing industrial materials for the making of his furniture. Like Le Corbusier, Herbst was trained as an architect and was greatly interested in creating products for modern living. Although a major proponent for the inclusion of new technology into the production and structure of furniture, Herbst was not against the continued use of wood, which he stated in an interview for Le Figaro Illustre, “Metals and all the plastics have not killed off wood. Wood will always find a place in certain interiors…Steel is good in its place but not everywhere.”[xxvii] Nevertheless, one place where Herbst utilized solely industrial materials was in his design of the Sandows Chair. Made out of nickel-plated tubular steel, springing, and plastic cords, the Sandows Chair provides comfort through ergonomics, an area of study that was especially researched during the postwar period.[xxviii] Despite the use of such modern materials, Herbst was also inspired by the well-worn seats found in the arenas of ancient Roman ruins.[xxix]Although the Sandows Chair does not reflect the French cabinetmaking tradition, like Ruhlmann’s Dressing Table Chair, the form was indirectly inspired by the past. The Sandows Chair appeared in several showrooms including the 1929 Salon d'Automne as well as the Aga Khan’s private Parisian residence, c.1930-1933.[xxx] During the joint effort in 1935 of Herbst, Le Corbusier, and Louis Sognot to design an apartment for a “young man” in Brussels, Sandows Chairs appeared in the exercise room (fig.14), which highlighted the popular association between metal and hygiene. [xxxi]

In examining the components of the Sandows Chair, some of the advances in modern technology during the interwar period are evident. The serpentine, tubular steel framing of the chair is evocative of the Chaise Longue by Corbusier, Perriand, and Jeanneret. One critic even compared the Sandows Chair to “bicycle handlebars,”[xxxii] and although it was intended as a negative comment, it nevertheless reveals the close link steel had to industry and not craft. Herbst had the novel idea of incorporating rubber strips that were stretched taut to provide comfort and support in the seating. Herbst declared that the elastic cords “mold exactly to the form of the body”[xxxiii] which followed the trend in ergonomic research. These elastic cords were connected to the steel frame by a series of metal springing with hooks. In the past, metal springing had been used in seating furniture as part of the underlying structure, and it was not visibly seen in the finished object.[xxxiv] Not only is the metal springing of the Sandows Chair visible, it functions both structurally and decoratively. By allowing the structure to provide visual interest through the materials used, Herbst successfully pared down the design of his chair into pure use. Unlike the Chaise Longue by Corbusier’s team, the Sandows Chair was successfully mass-produced and thus reflected the gradual acceptance of new metal furniture by the French consumer before the beginning of World War II.

At the same time Moderne designers such as Le Corbusier and Herbst were experimenting with industrial materials for seating furniture, more traditional materials such as textiles continued to be produced. For example, the ocean liner Normandie (1935), a flagship for French prestige and a symbol of national modernity, had more conventional furniture. In particular, Bouwens and Expert oversaw the interior design of the Grand Salon for first class passengers. They commissioned Maurice Rothschild to design the chairs and banquettes that were then made by Baptistin Spade.[xxxv] Also, the tapestry manufacturers of Aubusson produced both the seating upholstery for these seats and the large carpet covering the main floor. The sense of abundance that sets the decorative tone of the Grand Salon can be found in the red upholstery adorning the chairs and banquettes, which include the popular Art Deco image of flower bouquets in the textile design. While the floral theme of the Grand Salon’s furnishing may not have been inspired by any particular past source, this traditional ornamentation most likely provided a sense of familiarity making it a welcoming space for the first-class passengers.

In addition to metal and rubber, industrial glass was another modern material with which furniture designers experimented. The main producer of glass in France was the Saint-Gobain factory. Saint-Gobain was initially established as a manufacturer of mirrors in the seventeenth century and experienced a “Golden Age” during the nineteenth century and continued to evolve in the early twentieth century by producing hollow glass for bottles and flasks.[xxxvi] After World War I, Saint-Gobain developed a new form of safety glass. Through a process of extreme heating and rapid cooling. So called “tempered glass” was four to five times stronger than standard glass. During the 1937 Colonial Exposition in Paris, Saint-Gobain had their own glass pavilion to promote their newly created tempered glass. René Coulon was commissioned to create tempered glass furniture for the interior. Since tempered glass was such a sturdy material, Coulon was able to design a Chair entirely made out of glass with only metal studs joining the glass panes together. The translucence of the Chair made it a novel piece much admired by the public. Thus, the all-glass made Chair was a virtuoso piece in technical achievement and design innovation.

During the 1920’s and 1930’s, France was an imperial nation, which acknowledged its cultural past while simultaneously looking towards the future. Traditional materials, such as wood and textile, continued to be used but often in an ahistorical manner. Meanwhile, exoticism manifested itself in materials imported from the colonies including shagreen, ivory, and lacquer. The advances in industrial technology greatly influenced rationalist designers to adapt materials like metal, rubber, and glass into their furniture for twentieth century society. Through the integration of traditional, exotic, and industrial materials into furniture making, Art Deco designers were able to convey aspects of modern life through the visual and tactile materials they employed. Thus the concept of the “seat” during interwar period in France had a variety of responses as demonstrated by the wide range of seating furniture that was available.

Enjoyed reading? Subscribe to our newsletter.

Ahlstrom Appraisals | Personal Property Appraisals and Art Consultations | Serving Atlanta & Southeast | Fine Art, Antiques & Vintage

[i] David Raizman, History of Modern Design (London: Laurence King Publishing Ltd, 2003), 147.

[ii] Art Deco Furniture, 12.

[iii] Alastair Duncan, Art Deco Furniture (London: Thames and Hudson, 1984), 13.

[iv] Florence Camard, Ruhlmann: Master of Art Deco (New York: Harry N. Abrams, Inc., 1984), 45.

[v] Hans Huth, Lacquer of the West: The History of a Craft and an Industry: 1550-1950 (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1971), 1.

[vi] HDA course: Art Nouveau to Art Deco: class notes (January 2011), np.

[vii] Frederick Brandt, Late 19th and Early 20th Century Decorative Arts. Richmond: University of Washington Press, Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, 1985), 166.

[viii] The image provided is not the sofa originally found in Suzanne Talbot’s 1920 apartment, but is nonetheless a very similar piece.

[ix] J. Stewart Johnson, Eileen Gray: Designer (New York: Debrett’s Peerage Ltd., 1980), 17.

[x] Marianne Webb, Lacquer: Technology and Conservation (Boston: Butterworth-Heinmann, 2000), 47.

[xi] Late 19th and Early 20th Century Decorative Arts,166.

[xii] “African Forms in the Furniture of Pierre Legrain,” http://africa.si.edu/exhibits

/legrain/PEL.htm. Accessed January 31, 2010.

[xiii] Ibid.

[xiv] Lucy Trench ed., Materials and Techniques in the Decorative Arts: An Illustrated Dictionary (London: John Murray, 2000), 436.

[xv] Ibid.

[xvi] Late 19th and Early 20th Century Decorative Arts, 184.

[xvii] Art Deco Furniture, 99.

[xviii] class notes (January 2011), np.

[xix] Benton, Charlotte Tim Benton and Ghislaine Wood. eds. Art Deco 1910-1939. London: V&A Publications, 2003. 146

[xx] Ruhlmann: Master of Art Deco, 12-14.

[xxi] Ibid., 52.

[xxii] History of Modern Design, 164.

[xxiii] Clive D. Edwards, Twentieth-century Furniture: Materials, manufacture and markets (New York: Manchester University Press, 1994), 35.

[xxiv] Le Corbusier, “L’Aventure du mobilier” in “Charlotte Perriand: An art of Living by Mary McLeod ed. (New York: Harry N. Abrams, Inc., 2003), 48.

[xxv] Mary McLeod ed., Charlotte Perriand: An art of Living (New York: Harry N. Abrams, Inc., 2003), 48.

[xxvi] class notes (January 2011), np.

[xxvii]Guillemette Delaporte and Guillemette Delaporte-Idrissi, René Herbst: pioneer of modernism (New York: Flammarion, 2004), 101-102.

[xxviii] Ibid., 127.

[xxix] Ibid.

[xxx] Ibid., 101.

[xxxi] Ibid.

[xxxii] Art Deco Furniture, 100.

[xxxiii] René Herbst: pioneer of modernism, 127.

[xxxiv] Materials and Techniques in the Decorative Arts: An Illustrated Dictionary, 34.

[xxxv] John Maxtone-Graham, Normandie: France’s Legendary Art Deco Liner (New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 2007), 12.

[xxxvi] “Saint-Gobain (1665-1937): An Enterprise in the Face of History,” http://www.musee-orsay.fr. Accessed January 31, 2010.