Lady Invention patriotically dressed in red, white, and blue gestures to the distraught Chinese laundryman to leave, as his services are no longer required in America. Uncle Sam, who happens to be wearing celluloid cuffs and collars, witnesses the event with satisfaction while a sign in garbled English appears above him saying “Gon up Chinese Laundry.” To the twenty-first century observer, such a description suggests a political cartoon instead of an advertisement for clothing. Yet what has been described is the provocative and controversial image for a trade card promoting celluloid cuffs and collars during the 1890s.

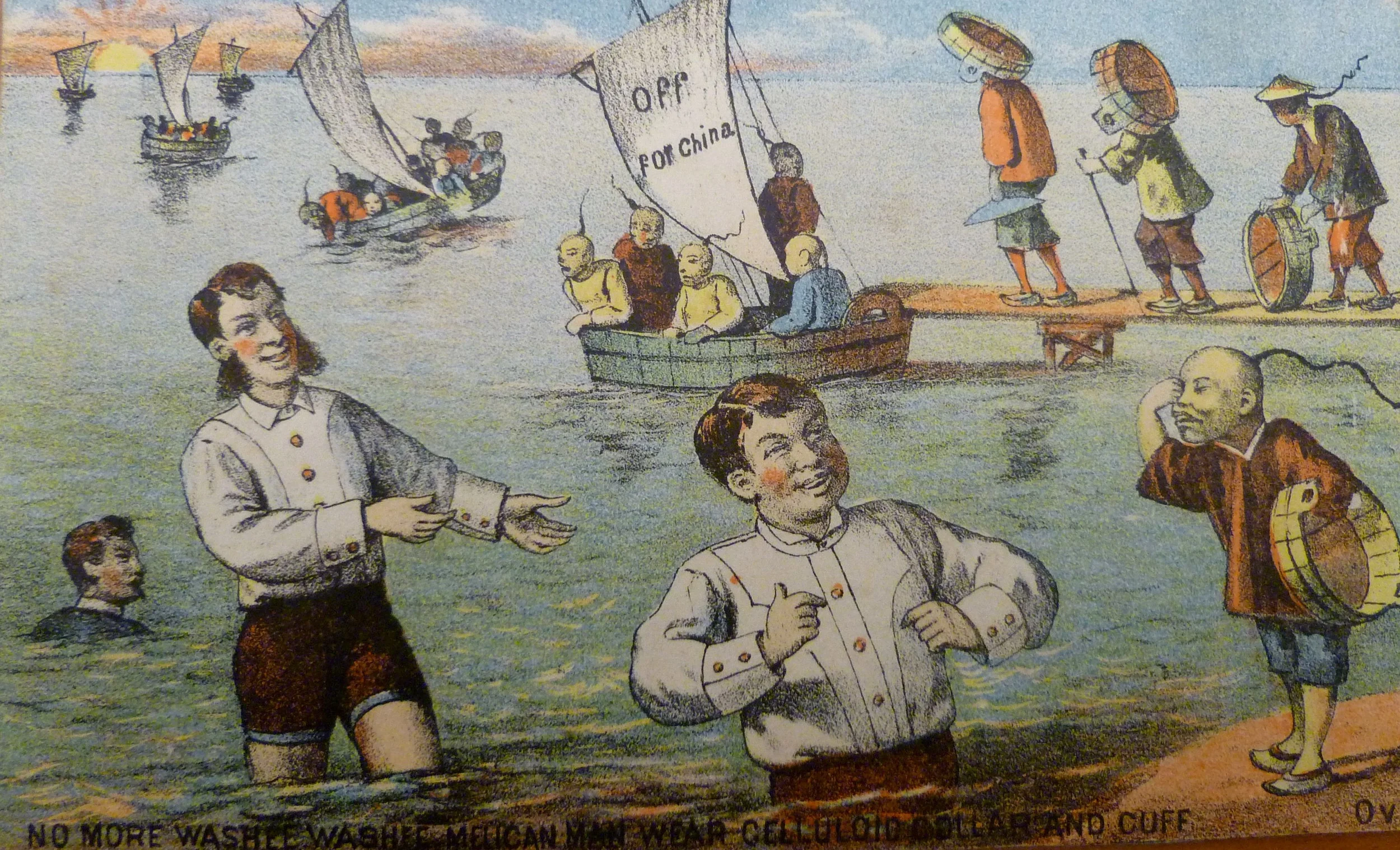

For historians, trade cards from the nineteenth-century reveal not only information about the products being advertised but also the cultural attitudes of the period. In particular, the visual line between commercial advertisement and political satire was far from being clear-cut at the end of the nineteenth century in America. The Archives of American Art has a collection of Celluloid Company’s trade cards for celluloid collars and cuffs that are an intriguing examples of an intersection between product advertising and social commentary. The Celluloid Company promoted their clothing articles by using two main arguments: the benefits of celluloid as “waterproof linen” and that these articles did not require laundering, specifically by the Chinese. Such advertising emphasizing the negation of Chinese laundries by purchasing celluloid collars and cuffs reveals a widespread prejudice among middle-class Americans against Chinese immigrants. Trade cards such as “No More Chinese Cheap Labor” (circa 1890) provide insight into the emerging middle class of nineteenth-century America, which catered to the social mobility of “white collar” workers but not to the Chinese launderers who had made those linen collars oh so white.

The association between the whiteness/cleanliness of clothing and one’s social status has a long history in Western costume. Indeed, there was a fetish for clean clothes that were “white white white” as early as the sixteenth century with the discovery of starch in 1554.[i] Since maintaining the whiteness of one’s white linens required constant laundering, there was a price to pay to keep up one’s fashionable appearance, which initially could be only afforded by the upper classes. Before the white collar became a sign of professionalism in the latter part of the nineteenth century, it had been a sign of gentility at the end of the eighteenth century among men of the upper class. Even in the early 1800s, the English dandy George “Beau” Brummell promoted the wearing of white articles of clothing as an indication of status. As the collar and cuff gradually replaced the cravat and lace at the wrists, the connection between whiteness of men’s clothing and status continued.

The laundry industry was therefore a prosperous business with the heyday for the laundry trade in the second-half of the nineteenth century. There was a diversity of people who capitalized on others’ desire to have clean clothes and linen without the drudgery of doing it oneself.[ii] Many recent immigrants to the United States became involved in the laundry business especially the Chinese who quickly dominated the profession throughout the American West. In his study The Chinese Laundryman: A Study of Social Isolation, social historian Paul Siu explains that the reason why so many Chinese immigrants chose professional laundering was because of racial discrimination by Euro-Americans in prohibiting them to participate in other type of labor besides mining and railroad construction.[iii] In fact, the majority of Americans was strongly against the presence of Chinese in the United States and attempted many boycotts on their products and services but to no avail.[iv] After all, Chinese laundry was still cheaper than their non-Asian competitors. Even Mark Twain commented that in Comstock, Nevada, the Chinese laundry’s “price for washing was $2.50 per dozen- rather cheaper than white people could afford to wash for at the time.”[v]

A lithograph from Harper’s Weekly in 1877 demonstrates the tension between Chinese laundrymen and their Euro-American customers. Depicted is a “typical” Chinese laundry house located in Virginia City’s Chinatown in which starching and ironing practices are unconventional and much objected to by their 'white' customers. They are particularly worried about their technique of spraying water and starch from one’s mouth onto clothes as represented in the lithograph below. In reality, the starching process actually involved blowing air through a tube filled with water. Nevertheless, patrons feared disease from such unsanitary practices especially when the main function was cleanliness.[vi]

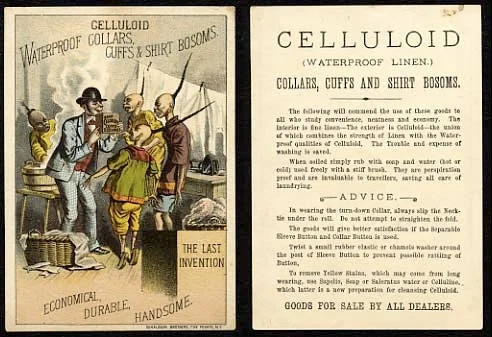

During the 1860s, John Wesley and Isaiah Hyatt developed and patented a new material called “celluloid.” By 1872, the Celluloid Company was established to manufacture and sell a variety of goods made of this new material. Celluloid is a tough, highly flammable substance consisting essentially of cellulose nitrate and camphor.[vii] Since celluloid can be easily molded, is waterproof, and resistant to being soiled, a variety of celluloid objects were produced ranging from baby rings, records, brushes, to faux-ivory figurines. Celluloid’s characteristics made it an ideal material for collars and cuffs. Yet, the Celluloid Company did not rely solely on celluloid’s qualities when promoting their collars and cuffs to the public. In addition, the company exploited the conflict between American customers and Chinese laundryman to maximize the chance of their celluloid goods being bought. Their trade card was the main marketing tool used to advertise their celluloid product.

While the trade cards promoting celluloid collars and cuffs portrayed several themes from circus acts to playful frogs, the most common subject involved the parody of distraught Chinese laundrymen. For example, one trade card depicts a travelling salesman displaying his new product of celluloid cuffs, collars, and shirt bosoms much to the shock of the gathered Chinese laundrymen as indicated by their black ponytails standing straight up as if they were the tails of startled black cats. Among all these trade cards that stereotype the Chinese, the basic accoutrements of laundering are also depicted: wooden tub, flat iron, and starch. Frequently, these laundry objects are often incorporated into trade card images as props for the Chinaman’s demise: the tubs are converted into boats to sail back to Asia in “Off to China” or the fallen box of starch as a sign for unemployment in “No Need for Chinese Cheap Labor.” Another common feature on these cards is the incorporation of broken English into the text. For instance in “Off to China,” the Chinese man’s response to the American man’s new wears appears at the bottom of the card: “No more washee washee, melican man wear celluloid collar and cuff.” The advertiser’s translation of the perceived Chinese accent into text reinforces the foreign characterization of the Chinese laundrymen and emphasizes their alien state in the Anglo-American culture of the nineteenth century.

In contrast to the negative representation of the Chinese in the Celluloid Company trade cards, the characterization of the Japanese can be considered more benign. Several factors contributed to the more positive depiction of the Japanese. Unlike the significant number of Chinese immigrating to America, very few people from Japan were emigrating from their homeland. In fact, Japan as a nation had recently reopened in 1854 to international trade and direct global interaction. Since Japanese citizens were experiencing economic prosperity, there was little need to migrate elsewhere. Partly due to the long period of cultural isolation, the Japanese in the eyes of Westerners had an aura of mystique, which was further encouraged by the fine art world’s development of japonisme. American artists such as James Whistler and John La Farge emulated elements of Japan’s visual lexicon into their own artworks. This fascination with all things Japanese translated into graphic art including celluloid trade cards.

For example, one of the trade cards for celluloid wares depicts a geisha-like figure is dressed in a kimono-like attire. The scene is evocative of Japanese woodblock prints that were highly desired by many Europeans and Americans artists and collectors during the late nineteenth century. The fanciful geisha's costume is accented with celluloid cuffs, collars, and shirt bosoms. Even her umbrella and shoes are made from celluloid cuffs, demonstrating their waterproof protection from the rain. Unlike the stock character of the savage Chinese laundryman, the Japanese caricature created by the celluloid advertisers recalls more doll-like features with an exotic appeal. This Japanese style found in advertisement was often treated as a humorous exercise in foreign imagery while echoing a long tradition of chinoiserie.[viii] By comparing the differing visual treatment of the Japanese and Chinese in celluloid trade cards, it is evident that Euro-American prejudice was not against “Orientals” but rather those who were “invading the nation.”

By the time the trade card “No More Chinese Cheap Labor” was produced, racial discrimination against the Chinese in America was at its height. Chinese immigration increased significantly from 1850 to 1880; by 1870, Chinese people compromised twenty-five percent of the work population in California. Riots against the Chinese broke out along Pacific Coast in the 1870s with the Workingmen’s party making it a goal to get rid of Chinese labor “as soon as possible.” The American West was not the only region that disliked the Chinese; in the Northeast by the 1870s, factories began hiring Chinese workers often as strikebreakers creating further racial tensions. As result of ethnic animosity, the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1883 barred additional Chinese from entering the nation and provided that those who were already in the country were ineligible for citizenship.[ix]

With the widespread belief that the cheap labor of the Chinese was an economic threat to America, the imagery of the trade card “No More Chinese Cheap Labor” is relevant to the political climate of the period. In addition to the disreputable Chinese caricature and the personifications of America as Lady Invention and Uncle Sam, several captions underscore the expected downfall of the Chinese laundry business. One phrase in particular is striking: “Othello’s occupation gone.” The reference to Shakespeare’s Othello parallels the protagonist’s loss of livelihood to the Chinaman's future. Such a reference to English literature on a trade card provides a contrast to the broken English written for the Chinese character. The script also flatters the potential customer as being a more civilized and educated than a launderer since he can understand such a literary allusion. “No More Chinese Cheap Labor” visually reads more like a political satire than a product promotional tool.

Although hurt at the time by the availability of celluloid collars and cuffs, the Chinese laundry business continued in America. For those who could afford laundering services, a white linen collar was preferred. Even in 1929, the stiff white collar –made of linen and not celluloid- signified a fashionable man. According to a 1920s survey of apparel worn by the three hundred best-dressed men in Palm Beach, everyone preferred to be a “slave to starch” and convention.[x] Thus, the celluloid collar and cuff did not eradicate its competition. Rather, the linen collar continued to be a sign of the well-to-do gentleman while the celluloid collar was more closely aligned with the aspiring middle-class.

As demonstrated by examining the Archives of American Art collection of celluloid trade cards from the 1890s, advertising provides valuable cultural insight into the relevant time period. At the end of the nineteenth century, social mobility was limited to Euro-Americans. Despite the many exclusions faced by Chinese immigrants, many “white collar” workers were still threatened by their presence in the workforce. The Celluloid Company used this xenophobia to their advantage by advertising celluloid collars and cuffs as a substitute, and perhaps a means to eradicate the Chinese laundry business. These trade cards captures the spirit of the Celluloid Company marketing strategy for selling clothing articles. Through the purchasing of celluloid collars and cuffs, there was no more need to constantly wash, no more need to professionally launder, and no more need for Chinese cheap labor. In other words, there was no more need for “washee washee.”

Enjoyed reading? Subscribe to our newsletter.

Ahlstrom Appraisals | Personal Property Appraisals and Art Consultations | Serving Atlanta & Southeast | Fine Art, Antiques & Vintage

[i] Aritha van Herk, “Invisble Laundry,” The University of Chicago Press 27 no. 3 (2002): 894.

[ii] Ibid., 895.

[iii] Ronald James, Richard Adkins, Rachel Hartigan, “Competition and Coexistence in the Laundry: A View of Comstock,” The Western Historical Quarterly 25 (1994): 164-167.

[iv] Ibid., 164.

[v] Ibid., 168.

[vi] Ibid., 170.

[vii] Dictionary.com, dictionary http://dictionary.reference.com/browse/celluloid.

[viii] Henry Adams “John La Farge’s Discovery of Japanese Art: A New Perspective on the Origins of Japonisme,” The Art Bulletin 67 (1985): 468.

[ix] Robert Jay, The Trade Card in Nineteenth-Century America. Columbia (University of Missouri Press, 1987), 72-73.

[x] Jenna Weissman Joselit, A Perfect Fit: Clothes, Character, and the Promise of America (New York: Metropolitan Books, 2001).