“The Americans adopted a more pragmatic stance in relation to the ideals of the Arts

and Crafts Movement and were, as a result, more commercially successful”- Unknown

It is interesting to suggest that American designers were the "pragmatists" of the Art and Crafts style considering that the movement's main objective in every nation was to produce objects that were simple and useful. The movement’s founders Ruskin and Morris desired the creation of ‘honest’ furniture both in material and quality. Accordingly, both English and American Arts and Crafts designers approached their work in a similar way with a commitment to truth to materials and to solid construction. So what was so especially pragmatic about the American Arts and Crafts Movement if both sides of the Atlantic were striving for good quality and overall simplicity? The answer lies in their differing responses to the ‘machine.’ While the English Arts and Crafts designers were antagonistic towards industrialism and the use of machinery during production, the American branch of the movement was less concerned with the moral connotations of industrial labor and thus more willing to incorporate the use of simple machines into the making of objects. In examining the endeavors of several Arts and Crafts furniture makers in the United States at the beginning of the twentieth century, the adaptation of the Arts and Crafts ethos to the realities of a growing industrial and capitalist society demonstrates the unique American formula for the Arts and Crafts Movement, which often resulted in commercial success.

As mentioned, Ruskin and Morris were key figures in formulating the philosophy of the movement that included the rejection of machinery in favor of handcraftsmanship. Groups, such as Ashbee with his Guild of Handicraft and even Morris himself with Morris and Company, attempted to apply this anti-industrial dogma to their practices with the result of creating a wide variety of handcrafted objects that were labor intensive and therefore expensive. Thus, one of the many theoretical dilemmas of the Arts and Crafts Movement arose: how to create high quality, handcrafted goods available for everyone at an affordable price. Ashbee tentatively allowed machinery to be used in his furniture making but mainly for cutting up the wood, and consequently labor costs were minimally reduced.[1] With a few exceptions, most English Arts and Crafts designers chose not to compromise their ideal of handcraftsmanship resulting in either works that were bought only by the wealthy (in the case of Morris and Company) or in endeavors that became financially unsuccessful (such as the Guild of Handicraft). The ideals of Morris and Ruskin in their most utopian form were no match for an emerging consumer culture. [2] Neverthless, Ruskin and Morris were influential, and in fact, they had great impact on developing the aesthetic identity of early twentieth century America since designers and reformers alike read their essays and admired their work.

America was not the first nation to mass-produce Arts and Crafts goods. In 1875, Arther Lasenby Liberty of London founded Liberty and Company in order to capitalize on the growing popularity of the Arts and Crafts movement by making affordable, mainly machine-made pieces. Liberty and Company even hired Arts and Crafts designers, such as Voysey, to provide designs that were then standardized for large-scale production. Although the English purists of the Arts and Crafts Movement disdained the combining of craft with manufacturing, Liberty and Company set an economic precedent that would later characterize the American approach to the movement.[3]

While American intellectuals and designers were aware of the Arts and Crafts philosophy, it was business entrepreneurs such as Gustav Stickley who brought the movement to the consciousness of the American middleclass. During his travels in England in 1896, Sitckley met the surviving figures of the Arts and Crafts Movement including Ashbee and Ambrose Heal; Stickley had even bought pieces of Voysey furniture thus spiritually and literally carrying home with him the philosophy of the movement.[4] Sitckley’s zeal for the Arts and Crafts emphasis on craftsmanship and a communal working environment manifested itself in the creation of the Gustav Stickley Company in 1899 (which later became known as the Craftsman Workshop) and the formation of the United Crafts guild in Eastwood, New York. However, Stickley’s passion for reviving a medieval form of production and an idyllic community gradually dissolved as the success of his business grew.

Stickley’s dilution of the Arts and Crafts philosophy in exchange for a larger scale of commercial success is exemplified by the Craftsman Workshop’s version of the Morris chair. Since the Morris chair in the public mind stood for manly comfort with its cushioned upholstery and adjustable back, nearly every manufacturer in the New York furniture exchange created versions of this English chair.[5] Stickley manufactured a reinterpretation of the Morris chair as well called the Reclining chair of 1906 in which the comfortable aspects of the original chair were heightened. For example, the arms of the Reclining chair are at a slight angle which echoes the reclining back and further adding to the object’s sense of repose. Instead of using traditional techniques of riving as would have most likely been used in the original Morris chair, the making of the Reclining chair involved quarter-sawn white oak, a technique in which the wood is sawn parallel to its radial structure and thus providing an imitation of the pre-industrial technique of riving.[6] Also, the quarter-sawn technique leant itself more readily to mass production since the time to make each piece was shortened. Thus, the Reclining chair demonstrates how Stickley shrewdly capitalized on both the Arts and Crafts aesthetic and industrial production.

While England primarily had The Studio magazine to promote the Arts and Crafts ideals, the United States had numerous publications including House Beautiful and The Craftsman. In particular, The Craftsman was created by Stickley with the dual purpose of promoting the Arts and Crafts and more significantly to market his own wares to a wider audience. Stickley’s choice of the magazine as his literary form of communication was strategic since literacy was growing among the American population; however, these new readers did not want erudite literature which was too challenging but rather more easily understood illustrated magazines like The Craftsman.[7] The Craftsman quickly became popular and the financial success of the Craftsman Workshop grew exponentially. With such a high demand for Stickley’s furniture, the use of the machine in mass production shifted from being convenient to necessary for the company’s growing success.

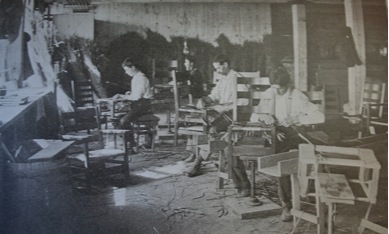

Although simplicity and utility were still the focus of Stickley’s philosophy, craftwork by hand was quietly aided by machinery. The somewhat disguised use of machinery can be seen in The Craftsman magazine in which the message communicated was that Craftsman furniture was individually handcrafted. Illustrations from the magazine further reinforced this notion of handwork such as the photographs of craftsmen working on chairs with no inclusion of the machines which were in fact actually used to die cut pieces. Ironically, in The Craftsman of October 1902, one of the articles declares, “Through these articles it was hoped to combat the spirit of commercialism which is the worst peril of our prosperous new country.”[8] Clearly Stickley was willing to play to the public’s ambivalence towards commercialism even if his own practice was “the worst peril.” While it can be argued that such marketing strategies, which emphasized handcraftsmanship and overlooked the use of machinery, were deceptive and not aligned with the Arts and Crafts mentality, the end products like the Reclining chair, were nonetheless of good quality and long lasting. Also Stickley’s commercial tactics allowed new ideas of beauty to be heard on a large scale which would have unlikely occurred if attention was given to the industrial aspects of the Craftsman Workshop.

Stickley began to experience a backlash toward his desire for expansion when he moved his headquarters to Manhattan. While production still continued in rural Eastwood, the rest of Sitckley’s business occurred in a twelve story office called the Craftsman Building which included a department store where customers would come to him, in addition to seeking his wares through catalogues. Interestingly, the Craftsman’s move from the countryside to the city is the reverse of Ashbee’s guild which left urban London for rural Chipping Camden; yet, both Ashbee’s and Stickley’s decision to move resulted in business failure. In 1916, Stickley declared bankruptcy. One explanation for Stickle’s sudden financial disaster was the waning popularity of the Arts and Crafts style amongst public taste which historian Barry Sanders vividly describes: “he [Stickley] continued to walk with the same methodical medieval step, while the band had switched to a fast paced jazz tune.”[9] Even though the Craftsman Workshop ended in bankruptcy, the furniture company nonetheless demonstrates the American trend to incorporate the Arts and Crafts into industry.

Elbert Hubbard from East Aurora, New York, was another entrepreneur who exploited the Arts and Crafts style for commercial gain with the Roycroft Shop. In an experiment similar to that of Ashbee’s guild in Chipping Campden, the Roycroft community was intended to foster a pre-industrial and communal atmosphere which included various craft shops, a library, a bank, a printing plant, etc.[10] A constant self-promoter, Hubbard created a persona of an eccentric who appropriated the craftsman ideal but in a way which distorted its spirit.[11] In contrast to the public image of the Craftsman Workshops, Hubbard did not hide the fact the machinery was used for part of the construction of Roycroft furniture. For example, in the catalogue of the books they published called Roycroft Books, photographs of the locals at work are included in which machinery can easily be seen in the background. Tourists even came to visit the quirky activity of East Aurora where they could stay in the Roycroft inn and buy souvenirs from the different shops. Whereas the Craftsman Workshop was pioneering on the business front of the movement in America, Roycroft was serving as a kind of arts and crafts amusement park.[12]

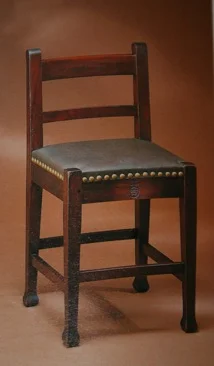

Despite the utopian image of the Roycroft community that Hubbard propagated, socialists of the period were enraged by the quasi-medieval community that in their view masked a reactionary corporate paternalism with low wages and open-shop practices.[13] Both Hubbard and Stickley promoted factory tactics in a ‘crafts’ environment such as the standardization of type objects and the division of labor in their production. But unlike Stickley who maintained a serious Art and Crafts commitment to quality of products and improved working conditions, Hubbard was interested in the Arts and Crafts façade alone as exemplified by the poor construction of the Roycroft furniture. For example, the Marshall P. Wilder chair is simple in its form but more crudely made in comparison with Stickley’s Reclining chair. This view of Hubbard’s lack of interest in the Arts and Crafts Movement beyond its potential as a marketing strategy is further reinforced by a comment Hubbard made to a friend in 1903: “The Roycroft began as a joke, but did not stay one; it soon resolved itself into a Commercial Institution.”[14]

In contrast to these New York businessmen’s superficial treatment of the Arts and Crafts ethos, Frank Lloyd Wright explored the movement’s principles as a designer. Although Wright never claimed to be apart of the American Arts and Crafts, historians often consider his contribution to the Prairie style during his early career as a facet of the movement. In particular, Wright was interested in the notion of the cohesion of the arts within the interior space. During the Oak Park period in Illinois, Wright began to experiment with the aesthetic unity of the architecture and furniture in a room by creating totally designed environments. Wright had two approaches to ensure that the furniture was in sync with the overall structure: built-in furniture or custom-made pieces. In particular, one of the custom-made chairs for the dining room of the Ward W. Willit House demonstrates the artistic unity of the space in which the horizontal emphasis of the dining room is balanced by the verticality of the chairs especially seen in the elongated back with its series of spindles.

The Willit dining room chair is also revealing of Wright’s attitude toward the machine’s role in the modern world. In contrast to Ruskinian belief which villainies the machine, Wright saw the machine as the “normal tool of civilization.” [15] In fact, the machine greatly influenced Wright’s furniture aesthetic of rectilinearity which could be quickly and inexpensively produced[16] as seen with the geometric shape of the Willit dining room chair. Wright initially employed John W. Ayers to produce his furniture designs like the dining chair; Ayers was a cabinetmaker with a small shop who was not only willing to use machinery for initial construction and then finish off the furniture by hand, but also tacitly accepted Wright’s progressive and uncommon aesthetic. Despite Wright’s approval of the use of the machine in making furniture, he did not look favorably on some of his contemporaries who were willing to industrialize the furniture process. In describing the furniture of Stickley and Roycroft, Wright called it “plain as a barn door;” although simple in its design and modern in its process, such furniture lacked the sophistication and subtleness of Wright’s own pieces.[17] While Wright may have been a proponent of the celebrated use of the machine in the making of modern furniture, his own pieces were limited editions for specific rooms and did involve some handcraft. Like Morris, Wright’s ideals did not often coincide with his own practice, yet both men provided a theoretical basis which had great influence on subsequent designers in the United States.

The Greene brothers of Pasadena, California, were another pair of architects who were fortunate enough to have several clients willing to have totally designed interiors with custom-made Arts and Crafts furniture. Although the Greenes began their architectural careers building conventional homes often in a historicist revival style, their client for the Culbertson house was (like the Greenes) interested in the Arts and Crafts style and thus fostered a climate for the Greene brothers to exercise their ideas. [18] During the “ultimate bungalows” period, the Greene brothers designed expensive homes that were made of the best material available and with the highest quality of craftsmanship. The Greenes can be seen as being parallel to Morris and Company in which both groups created objects of high craftsmanship for a wealthy clientele who were willing to pay the high cost of labor even for details like the Armchair of 1907-1909 for the Blacker house. Similar to Wright’s chair for the Willit house, the Greenes’ Armchair was specifically designed to fit the dining room of the Blacker home. The Armchair incorporated a variety of materials including mahogany, ebony, silver, mother of pearl, etc. thus displaying a form of Arts and Crafts which was interested in experimentation with materials and an exploration of new types of ornament such as the inlay on the back of the chair with its motif of stylized nature. Like the other American Arts and Crafts figures mentioned, the Greenes were different from the English movement in their willingness to use machinery. Although the Greenes’ furniture designs (produced by Hall’s workshop) are not tailored to a machine aesthetic as exemplified by their use of soft edges, the Greenes’ use of machinery does speak resoundingly to the validity of incorporating machine construction when harnessed to sound ideals.[19]

In discussing a few furniture makers of the American Arts and Crafts, it is clear that the Arts and Crafts philosophy was altered to fit into the industrial world that it had originally reacted against. In the United States, the movement had drawn to an interesting conclusion in which rather than craft and industry being polarized as the Arts and Crafts founders initially desired, the two forms of making had intertwined. While certain companies such as the Craftsman Workshop and the Roycrofters focused more on incorporating industrialization into the furniture process, architects like Frank Lloyd Wright and the Greene brothers used the machine for the sake of aesthetics. In all of these examples, the groups/designers experienced a degree of commercial success that provided a means for the Arts and Crafts principles to enter the mainstream and have a greater impact on the thinking, making, and consuming of design. While England had produced the idealists of the Arts and Crafts Movement, America provided its pragmatists.

Enjoyed reading? Subscribe to our newsletter.

© Courtney Ahlstrom Christy

Ahlstrom Appraisals | Personal Property Appraisals and Art Consultations | Serving Atlanta & Southeast | Fine Art, Antiques & Vintage

[1] Allen Crawford. C. R. Ashbee Architect, Designer, & Romantic Socialist. (London: Yale University Press, 2005), 219.

[2] Margaret Crawford. “Review: Arts and Crafts as an Ideological Myth,” Journal of Architectural Education, 44, no.1 (Nov. 1990), 60.

[3] Leslie Greene Bowman. American Arts and Crafts: Virtue in Design. (Westerham: Los Angeles County Museum of Art, 1990), 22.

[4] Barry Sanders. A Complex Fate: Gustav Stickley and the Craftsman Movement. (New York: John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 1996), 13-14.

[5] Eileen Boris. Art and Labor Ruskin, Morris, and the Craftsman Ideal in America. (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1986), 59.

[6] Leslie Greene Bowman. American Arts and Crafts: Virtue in Design, 71.

[7] Barry Sanders. A Complex Fate: Gustav Stickley and the Craftsman Movement, 67.

[8] Samuel Howe. “A Visit to the Workshops of the United Crafts at Eastwood, New York,” The Craftsman, 3, no.1 (October 1902), p. 59.

[9] Barry Sanders. A Complex Fate: Gustav Stickley and the Craftsman Movement, 167.

[10] Pamela Todd. The Arts and Crafts Companion. (London: Thames and Hudson, 2008), 22.

[11] Eileen Boris. Art and Labor Ruskin, Morris, and the Craftsman Ideal in America, 146.

[12] Leslie Greene Bowman. American Arts and Crafts: Virtue in Design, 42.

[13] Margaret Crawford. “Review: Arts and Crafts as an Ideological Myth,” Journal of Architectural Education, 61.

[14] Eileen Boris. Art and Labor Ruskin, Morris, and the Craftsman Ideal in America, 147.

[15] David Hanks. The Decorative Designs of Frank Lloyd Wright. (New York: E.P. Dutton, 1979), 41.

[16] Ibid., 37.

[17] Ibid., 36

[18] Edward Bosley. Greene and Greene. (London: Phaidon, 2000), 50.

[19] Leslie Greene Bowman. American Arts and Crafts: Virtue in Design, 46.